Huxley’s predictions on our common future might come true (English version at the end of this article)

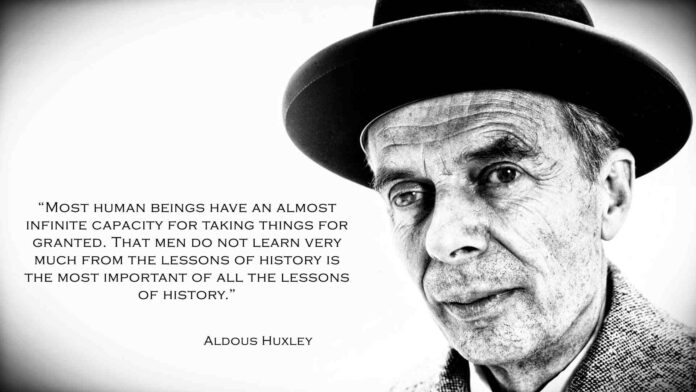

„Mi se pare că natura Revoluției finale cu care ne confruntăm acum este tocmai aceasta: că suntem în curs de dezvoltare a unei serii întregi de tehnici care va permite oligarhiei de control – care a existat dintotdeauna și probabil va exista întotdeauna – să-i facă pe oameni să-și iubească servitudinea”. Aldous Huxley, U.C. Berkeley (20 martie 1962)

Într-o societate a consumatorilor cum este cea de astăzi, merită citite cărțile vechi care sunt în afara curentului principal al culturii pop, să petrecem puțin timp cu noi înșine în solitudine și să reflectăm la ceea ce se întâmplă în lume? Ar fi atunci o pierdere de timp sau un timp câștigat?

Pentru Margaret Atwood, merită încă citit romanul lui George Orwell, 1984, și Minunata lume nouă a lui Aldous Huxley, deoarece ambele se referă la lumea noastră dincolo de ficțiune. În 1984, George Orwell își imaginează o societate totalitară controlată de cultul personalității Big Brother care, ca Dumnezeu din cer, știe tot ceea ce facem și unde suntem în fiecare moment. Precum imaginea răsturnată dintr-o oglindă, aici liberul arbitru al oamenilor este distrus de tortură, în timp ce în Minunata lume nouă, comportamentul dezirabil este obținut prin plăcere și recompensă.

„Ar fi posibil ca ambele viitoruri – cel dur și cel moale – să existe în același timp, în același loc? Și cum ar fi?” se întreabă Margaret Atwood în introducerea cărții lui Huxley (Margaret Atwood).

O muză pentru inspirație: Oameni ca zei

După căderea regimului stalinist și a Zidului Berlinului în 1989, toată lumea se aștepta în Europa, chiar și în Statele Unite, la scurt timp după criza Golfului Persic, la ani de pace și prosperitate eliberați de fantomele trecutului, ale războiului total și terorii. Această imagine idealistă se schimbă însă odată cu atacul asupra Turnurilor Gemene din New York în 2001, observă Atwood și pe bună dreptate: „Ministerul Iubirii a revenit cu noi, pare că, totuși nu se mai limitează la țările din spatele fostei Cortine de fier: Occidentul are propriile sale versiuni acum” (Atwood).

Într-adevăr, basmul se schimbă mai ales după ce Junior Bush îndeamnă poporul american să meargă și să cumpere mai mult pentru a combate terorismul. Pentru mulți americani, această cerere a apărut ca „în maniera unui monolog de comediant de noapte târziu despre „cât de prost poate fi cineva să creadă că cumpărăturile sunt un răspuns la terorism?” ”(Peter D. Feaver).

Americanii nu și-au putut ascunde indignarea. Dar întrebarea nu este cât de prost poate fi cineva, mai degrabă dacă ni se joacă o comedie neagră, o farsă de atunci? La urma urmei, nu era tatăl său, seniorul George H.W. Bush, care ne-a spus în 1990 că o nouă Ordine Mondială va apărea odată cu războiul împotriva terorismului?! Și nu am pășit într-o lume nouă odată cu 11 septembrie 1990 sau 2001?

Ei bine, tocmai această imagine răsturnată a unei lumi idealizate va fi contestată în secolul trecut de un scriitor tânăr și rebel care a îndrăznit să pună la îndoială ideea progresului științific și tehnologic prin fabula sa scrisă: Brave New World. Ce l-ar fi putut inspira pe avangardistul Aldous Huxley care a fost cu un pas înainte față de oamenii epocii sale și care a anticipat atât de bine viitorul mai puțin luminos pe care ni-l va aduce această lume nouă? Contextul politic și social în care s-a născut fără îndoială. Regizorul de teatru James Dacre, care a transpus pe scenă povestea sa, subliniază într-un articol pentru The Guardian:

„Aldous Huxley a scris Brave New World în 1931 în umbra Primului Război Mondial, a Crash-ului de pe Wall Street și a unui virus de gripă devastator care a luat milioane de vieți. Tratatul de la Versailles sculptase o nouă Europă, în timp ce electricitatea, automobilul, liniile de producție, noile mijloace de comunicare în masă și avioanele schimbau lumea. Anglia se afla sub stăpânirea unei depresii, dar știința și tehnologia promiteau un viitor mai bun: o lume în care boala, truda și sărăcia ar putea să nu mai existe. Foarte puțini scriitori au fost suficient de îndrăzneți pentru a contesta acest optimism naiv, dar în Brave New World, Huxley a făcut-o cu siguranță;” (James Dacre).

Un alt lucru au fost dezbaterile de epocă în jurul rolului științei și tehnologiei asupra societății, în special a tehnologiilor de reproducere. Discuții care erau la modă în acea vreme mai ales după eseul publicat de J. B. S. Haldane „Daedalus, sau știința și viitorul” din 1924.

„Minunata lume nouă a lui Huxley s-a bazat puternic pe tehnologiile pe care Haldane le-a prognozat în eseul său Daedalus, sau știința și viitorul (1924), în special ideea ectogenezei – gestația embrionilor și a fetușilor în containere artificiale.

(…) Deci Brave New World nu a apărut de nicăieri, ci a fost o contribuție la o dezbatere viguroasă interbelică despre influența științei asupra societății, nu în ultimul rând rolurile tehnologiilor de reproducere. Această dezbatere a fost exemplificată de seria de eseuri de azi și de mâine – din care Daedalus a fost primul – publicat în Marea Britanie de Kegan Paul între 1923 și 1931” (Philip Ball).

Ca un gânditor liber, el și-a asumat o poziție destul de diferită de credințele membrilor familiei, prietenilor și concetățenilor. Fratele său, Julian Huxley și Haldane – unul dintre prietenii familiei – au fost co-fondatori ai Revistei de biologie experimentală. Totuși, muza de inspirație a lui Aldous Huxley pentru Brave New World nu a fost Daedalus-ul lui Haldane („Daedalus, sau știința și viitorul”), nici Icarul lui Bertrand Russell („Icarus, sau viitorul științei”), chiar dacă aceste două lucrări ar fi putut fi în mintea lui când a scris fabula.

Ceea ce îl inspiră cu adevărat este romanul Oameni ca zei al lui H. G. Wells. Îl inspiră, amuză și-l irită în același timp. Împotriva căreia își oferă propriul răspuns prin satira sa, parodia „Minunata lume nouă” (Caitrin Keiper). Dar „Oameni ca zei” nu este doar titlul unui roman. De asemenea, este o stare de fapt.

Când Huxley a trăit știința, progresul tehnologic, biologia experimentală păreau să promită omenirii „un viitor mai bun”. Copiii cu tuburi, fertilizarea in vitro, ideea concepției copiilor într-un pântec artificial nu mai era un mister pentru știință. Știința vine cu această promisiune eshatologică de mântuire de la moarte, boală, suferință, pe care oamenii au crezut-o. În laboratoarele lor, oamenii de știință se jucau de-a Dumnezeu. Afară, pe scena politică, dictatori care se ridică la putere precum Hitler și Stalin se comportă ca niște zei și sunt văzuți de masele de oameni ca zei pe pământ.

Prin scrierile sale, Huxley critică și ironizează tocmai această credință naivă într-un viitor mai bun promis de știință și tehnica avansată. În Cuvântul înainte din Brave New World Revisited (1958), el scrie că această a doua parte sau continuare a fabulei din 1931 „ar trebui citită pe fundalul gândurilor trezite de revoluția maghiară (din 1956) și de represiunea ei”, inventarea bombelor cu hidrogen; și a prețului plătit de toate statele în numele „apărării naționale”, de unde au apărut socialismul rus și naționalismul german care au dus la regimuri dictatoriale în secolul trecut (Aldous Huxley, 2011, 290). În timp ce, într-un răspuns trimis către UNESCO, scrie: „Știința aplicată pusă în slujba, mai întâi, a marilor afaceri și apoi a guvernului a făcut posibil statul totalitar modern”. Din acest motiv, ca și pentru multe altele, face un apel pentru un nou Proiect Manhattan, despre care credea că ar trebui să beneficieze marea majoritate a oamenilor, nu numai puterile centralizate cu elita conducătoare (Aldous Huxley, iunie 1947).

Ca într-o mișcare dialectică a istoriei, răspunsul la național-socialismul secolului trecut ar putea fi o ideologie globală, nu mai puțin inofensivă și radicală decât cele de până acum, având aceleași efecte devastatoare. Într-una dintre ultimele sale apariții publice, Huxley ne-a avertizat că sub presiunea unor forțe impersonale, cum ar fi creșterea populației și terminarea resurselor naturale, sau supraorganizarea și progresul tehnologic, acestea ar putea duce la descentralizarea puterii guvernelor. Și la concentrarea ei în mâinile unui mic grup de oameni, și anume al unei oligarhii, care ne va conduce spre o dictatură mondială, nu numai în Statele Unite (The Mike Wallace Interview, 1958).

„Minunata lume nouă” văzută prin ochii lui Aldous Huxley

Răsăritul și Apusul și-au cunoscut titanii în primul și al doilea război mondial, dar America avea și ea zeii săi. În anii ’20, Henry Ford, unul dintre cei mai bogați oameni din lume, era văzut ca un vizionar în interiorul și-n afara Americii. Ford era Dumnezeul Americii.

Proiectul său „Fordlandia” a avut ca scop cultivarea unei plantații de cauciuc în inima Amazonului brazilian pentru dezvoltarea afacerilor sale cu mașini. De asemenea, construirea unui întreg oraș, un oraș industrial în miniatură de tip Midwest. Exportarea modului de viață american în jungla Amazoniei. Era prevăzut să meargă atât de departe până la reglementarea chiar și a celor mai mici aspecte ale vieții private a angajaților. Aproape ca într-o societate totalitară, remarcă scriitorul și profesorul de istorie, Greg Grandin, într-un interviu televizat (Greg Grandin).

Mă întreb dacă proiectul său de a construi din temelii un oraș întreg, o lume civilizată în junglă, condusă de o Corporație și de legile sale economice, mai există astăzi?

Ce mai inspiră fabula lui Huxley este o „vizită la fabrica Billingham, o mare uzină de prelucrare chimică condusă de industriașul Alfred Mond” (COVE Editions). Baronul Mond și Henry Ford sunt două personaje cheie în povestea sa. Oare Huxley s-ar fi putut inspira atât din această vizită, cât și din proiectul lui Ford? Nu știm sigur, dar societatea descrisă în Minunata lume nouă seamănă în multe privințe cu societatea visată de Ford.

În Minunata lume nouă, acțiunea începe la Centrul de Incubație și Condiționare pentru Londra centrală, care se află sub „ochiul supraveghetor” al statului mondial, așa cum sloganul afișat la intrarea acestei clădiri gri de numai treizeci și patru de etaje arată: Comunitate. Identitate. Stabilitate.

Din păcate, Huxley nu ne spune prea multe despre modul în care funcționează guvernarea acestui stat mondial în afara Londrei. El vorbește doar despre o societate tehnologică avansată dintr-un viitor îndepărtat, anul 632 A.F. (2540 după Ford). Condusă de principiile cercetării științifice, progresul tehnologic și de legile economiei de piață. Și în care nu mai există președinți aleși, nici suzeranitatea unui stat. Doar zece controlori mondiali, ceea ce înseamnă că statul mondial este împărțit în zece regiuni cu puterea lor centralizată, cel mai probabil, în orașul Londra. Mustapha Mond (alias, baronul Alfred Mond în viața reală) este controlorul lumii rezidente pentru Europa de Vest. Întreaga lume nouă a lui Huxley ne oferă imaginea unei comunități globale unde oamenii de afaceri ca Alfred Mond și Henry Ford sunt zeificați.

În această societate avansată sunt mașini zburătoare pe cer. Trecerea de la o zonă geografică la alta se face cu elicoptere și rachete. Nicio urmă din vechiul mod de a călători. Mașini conduse pe asfalt, povești de adormit. Copiii nu mai sunt concepuți prin naștere naturală, ci în pântecele artificial. Reproducerea vivipară, căsătoria, văzute ca ceva obscen. Centrul de Incubație și Condiționare din Londra este un astfel de loc în care copiii se nasc artificial și sunt condiționați de la naștere până la moarte pentru a fi „fericiți” în casta din care aparțin Alpha, Beta, Gamma, și așa mai departe.

Afară, la marginea civilizației, sunt rezervații naturale locuite de sălbatici precum Rezervația New Mexico. Bebelușii încă se nasc acolo într-un mod natural. Comunitatea lor mică și săracă păstrează vechile tradiții legate de religie și căsătorie. Lucruri care în lumea civilizată sunt complet desființate, șterse din memoria colectivă. La fel ca istoria cu tot trecutul ei care stătea în spate.

„Istoria este suprapusă” în această lume nouă, spune Mond unui grup de studenți. Toată istoria, împreună cu înțelepciunea sa moștenită, de la Gautama Buddha la Homer și Iisus, este măturată. Literatura veche, fâș-fâș. Shakespeare, toată poezia interzisă. Trecută la Index Librorum Prohibitorum. La fel și Biblia. Este o carte interzisă, ascunsă într-un seif mare de Controlorul mondial pentru Europa Occidentală. Singura carte care este lăsată liberă să circule este „Biblia” lui Ford, biografia despre viața și opera sa, publicată pentru răspândirea cunoștințelor fordiene în lumea nouă (Aldous Huxley, 2011, 92, 250, 262. Vezi și ediția engleză, 2005).

„În roman, toată religia a dispărut și a fost uitată de cetățenii statului mondial. Singurele principii religioase sau asemănătoare divinității pe care oamenii le urmează sunt cele ale lui Henry Ford, inventatorul modelului T”(Derek D. Miller). Când Ford și-a introdus pe piață automobilul Model T, acest lucru a revoluționat industria transporturilor și a industriei americane. „Fordismul”, cu viziunea sa globală pentru o societate stabilă, în care productivitatea bunurilor ieftine și consumul lor oferă un nivel de viață mai ridicat, pune capăt conflictelor sociale, deci este cheia păcii și fericirii, a devenit noua religie a Americii la scurt timp după sfârșitul primului război mondial. Destul de asemănător, Huxley își imaginează o societate tehnologic avansată, cu mașini zburătoare, în care inventatorul și invențiile sale sunt divinizate de masele moderne.

În cuvintele lui Neil Postman, aceasta ar fi un „tehnopol” sau o „tehnocrație totalitară” în care toate formele culturale ale vieții, arta, religia, chiar și știința, sunt sacrificate pe altarul progresului tehnologic, pentru o fericire iluzorie. Astfel, oamenii nu mai sunt copiii adevăratului Dumnezeu, nici măcar cetățeni ai lumii, doar simpli consumatori.

În loc de concluzii. Trăim în Minunata lume nouă a lui Huxley?

Este această imagine a societății Model T decupată dintr-un film science-fiction? Poate că proiectul lui Ford și societatea imaginată de Huxley, cu orașul său din viitor, sunt mult mai aproape de noi decât am crezut vreodată. La urma urmei, trăim într-o societate de consum în care aproape toată lumea își permite să-și cumpere o mașină așa cum a visat Ford. Și datorită liniei moderne de asamblare și producție în serie, acum avem acces mai ușor la toate bunurile ieftine care ar trebui să ne facă să ne simțim „mai fericiți”. Dar poate fi redusă fericirea la simplul consum pentru plăcere? Deoarece asta este ceea ce avem astăzi: un consum pentru plăcere, nu numai pentru nevoile noastre. Devorăm bunurile pe care le cumpărăm mai repede decât canibalii. Zdranc la gunoi! Este un comportament canibal, dar mai mult este un comportament autodistructiv, de înstrăinare.

Consumul, în orice fel, este religia Lumii Noi. Fericirea nu mai este o căutare a individului, ci devine fericire socială, fericirea „de a merge la cumpărături”, cum a spus Bush după 11 septembrie, și poate că acest lucru o face atât de iluzorie. Dar tocmai aceasta era societatea visată de Ford și, desigur, de elită. O societate în care noua generație este programată neuro-lingvistic de propaganda mediatică (prin trucuri de marketing și retorică) să lucreze pentru statul mondial, corporațiile sale conducătoare și să consume mai mult. Totul devine suprafață, dar nu există profunzime în ea.

Buddha ar fi răspuns la iraționalitatea maselor (post) moderne: Rămâi în interiorul Sinelui, dacă nu vrei să te distrugi! Sinele, capacitatea interioară de interogare și de gândire liberă, este ceea ce orice guvern totalitar a încercat să distrugă. De aceea, în 1984 și Minunata lume nouă, solitudinea și iubirea adevărată (nu cea a Ministerului Iubirii) sunt condamnate. Deoarece prin gândire și iubire oricine se poate opune dictaturii, fapt care ar putea pune puțin în pericol structura ierarhică ce deține puterea. Oamenii sunt ținuți într-o paradă nesfârșită de distracții în Minunata lume nouă, astfel încât să nu știe niciodată că le-a fost luată libertatea, împreună cu alegerile și deciziile lor.

Divertismentul gratuit și consumul irațional urmăresc să distragă atenția oamenilor de la procesul deciziilor în care nu mai sunt implicați ca simpli consumatori. După cum nu sunt implicați în căutarea adevărului, pentru înțelegerea realității în care trăiesc. Adevărul devine irelevant, se temea Huxley. Într-adevăr, „ce rost mai are adevărul sau frumuseţea sau cunoaşterea, când de jur-împrejurul tău explodează bombe bacteriologice?” Totul a început să fie controlat de la Războiul de nouă ani, chiar și dorințele oamenilor, îi spune Controlorul occidental lui Ioan Sălbaticul (Aldous Huxley, 2011, 260).

Am putea întreba același lucru dacă lumea noastră nu se schimbă radical după evenimentele din 11 septembrie? Nu trăim într-o lume mai puțin liberă de atunci? Poate că Margaret Atwood avea dreptate când a sugerat că Occidentul vine cu propria versiune a totalitarismului. Că am putea trăi în ambele scenarii, ale acestor două lumi paralele, 1984 și Brave New World, în același timp.

Ultimele dispozitive tehnice pentru monitorizarea vieții private seamănă cu Big Brother din 1984. Nu mai este necesar ca un singur partid cu liderul său dictatorial să înrobească lumea, dacă controlorii mondiali pot face aceeași treabă pentru statul mondial dispunând de tehnologie. Oricât de nerealist ar părea Brave New World nu este pură ficțiune. Viziunea unei lumi împărțite în zece regiuni politice/economice sau regate poate fi găsită în raportul publicat de Clubul Romei din 17 septembrie 1973, numit „Modelul regionalizat și adaptativ al sistemului lumii global” (Pleasanton Weekly). În opinia mea, cred că această viziune este mult mai veche de atât, despre care, cel mai probabil știa Huxley.

Deci, da, predicțiile lui Huxley asupra viitorului nostru ar putea fi adevărate. Încă nu avem zece regiuni ale lumii, mașini zburătoare, copii născuți în pântece artificiale, dar este o chestiune de timp. Cele mai recente cercetări științifice din domeniul medical legate de uterul artificial arată că, în viitorul apropiat, am putea avea copii-tub, fertilizați și născuți în afara uterului matern, cum prevedea Huxley (Sahotra Sarkar). Cu atât mai mult cu cât cea mai recentă legislație privind educația sexuală adoptată la Bruxelles, cu accentul pus pe autonomia corpului uman, încurajează acest tip de cercetare (Rezoluția Parlamentului European, 24 iunie 2021).

Toate acestea, împreună cu guvernarea electronică din Estonia, primul oraș inteligent din viitor, Neom, lansat probabil înainte de 2050 în Orientul Mijlociu, sau Regatul Spațial al Asgardiei, arată că această lume nouă vine peste noi, indiferent dacă vrem, sau nu vrem, și că s-ar putea transforma peste noapte într-un coșmar terifiant.

Ana-Maria Caminski

Corespondent in Romania, pentru NASUL TV Canada

Huxley’s predictions on our common future might come true

“It seems to me that the nature of the Ultimate Revolution with which we are now faced is precisely this: That we are in the process of developing a whole series of techniques which will enable the controlling oligarchy – who have always existed and presumably will always exist – to get people to love their servitude.” Aldous Huxley, U.C. Berkeley (March 20, 1962)

In a consumer society like today, worth reading old books that are out of the mainstream of pop culture, to spend a little time with ourselves in solitude and reflect on what is happening in the world? Would it be then a waste of time or a gained time?

For Margaret Atwood, still worth reading George Orwell’s novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World because both relate to our world beyond fiction. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell imagines himself a totalitarian society controlled by the cult of Big Brother personality who, as God from the sky, knows everything that we are doing and where are we in every moment. Like the overturned image from a mirror, here people’s free will is destroyed by torture, while in Brave New World, desirable behavior is obtained by pleasure and reward.

“Would it be possible for both of these futures – the hard and the soft – to exist at the same time, in the same place? And what would that be like?” wonders Margaret Atwood in the introduction of Huxley’s book (Margaret Atwood).

A muse for inspiration: Men like Gods

After the falling down of the Stalinist regime and of the Berlin Wall in 1989, everybody expected in Europe, even in the United States, soon after the Persian Gulf crisis, to years of peace and prosperity liberated from the ghosts of the past, of total war and terror. This idealistic image changes however once with the attack on New York City’s Twin Towers in 2001, notice Atwood and rightly so: “The Ministry of Love is back with us, it appears, though it’s no longer limited to the lands behind the former Iron Curtain: the West has its own versions now” (Atwood).

Indeed, the fairy tale changes especially after Junior Bush urges the American people to go and shop more so that they combat terrorism. To many Americans, this demand appeared as “in the manner of a snarky late-night comedian’s monologue about „how dumb can someone be to think that shopping is a response to terrorism?” ” (Peter D. Feaver).

Americans could not hide their indignation. But the question is not how dumb someone can be, rather if we are been played a black comedy, a hoax since then? After all, was not his father, Senior George H.W. Bush, who told us in 1990 that a New World Order will emerge once with the war against terrorism?! And we are not been stepping into a new world once with September 11, 1990, or 2001?

Well, precisely this overturned picture of an idealized world will be challenged in the last century by a young and rebellious writer who dared to question the idea of scientific and technological progress through his written fable: Brave New World. What could have inspired the avant-gardist Aldous Huxley who was one step further to the people of his Age and that has anticipated so well the less bright future this new world will bring to us? The political and social context in which he has born without doubt. Theatre director James Dacre, who transposed his story on stage, emphasis in an article for The Guardian:

“Aldous Huxley wrote Brave New World in 1931 in the shadow of the First World War, the Wall Street Crash, and a devastating flu virus that had claimed millions of lives. The Treaty of Versailles had carved out a new Europe, while electricity, the automobile, production lines, new mass media, and airplanes were changing the world. England was in the grip of a depression, but science and technology promised a better future: a world where disease, drudgery, and poverty might no longer exist. Very few writers were bold enough to challenge this naive optimism but in Brave New World, Huxley certainly did;” (James Dacre).

Another thing was the epoch debates around the role of science and technology on society, especially reproductive technologies. Talks that were en vogue at that time most of all after the published essay of J. B. S. Haldane ‘Daedalus, or Science and the Future’ in 1924.

“Huxley’s brave new world leaned heavily on the technologies that Haldane had forecast in his essay Daedalus, or Science and the Future (1924), particularly the idea of ectogenesis — the gestation of embryos and fetuses in artificial containers.

(…) So Brave New World did not appear out of nowhere, but was a contribution to a vigorous interwar debate about the influence of science on society, not least the roles of reproductive technologies. That debate was exemplified by the To-day and To-morrow essay series – of which Daedalus was the first – published in Britain by Kegan Paul between 1923 and 1931” (Philip Ball).

As a free thinker, he assumed a quite different position from the beliefs of family members, friends, and fellow citizens. His brother, Julian Huxley, and Haldane – one of the friends of the family – were co-founders of the Journal of Experimental Biology. Still, Aldous Huxley’s muse of inspiration for Brave New World was not Haldane’s Daedalus (‘Daedalus, or Science and the Future’), neither Bertrand Russell’s Icarus (‘Icarus, or The Future of Science’), even if these two works could have been in his mind when he wrote the fable.

What really inspires him is H. G. Wells’s novel Men like Gods. It muses, amuses, and irritates him at the same time. Against which offers its own answer by his satire, parody ‘Brave New World’ (Caitrin Keiper). But ‘Men like Gods’ is not only the title of a novel. Also is a state of affairs.

When Huxley lived science, technological progress, experimental biology seemed to promise mankind ‘a better future’. Tube babies, fertilization in vitro, the idea of the conception of babies in an artificial womb was no longer a mystery for science. Science comes with this eschatological promise of salvation from death, illness, suffering, which people believed. In their labs, scientists were playing God. Outside, on the political scene, dictators that rise up at power such as Hitler and Stalin behave like Gods and are seen by the masses of people like Gods on Earth.

Through his writings, Huxley criticizes and ironizes precisely this naïve belief into a better future promised by science and advanced technique. In the Forward Word from Brave New World Revisited (1958), he writes that this second part or continuation of the fable from 1931 “should be read against the background of thoughts aroused by the Hungarian revolution (since 1956) and its repression”, of the invention of hydrogen bombs; and of the price paid by all the states in the name of ‘National defense’, from where the Russian socialism and German nationalism have appeared that led to dictatorial regimes in the last century (Aldous Huxley,2011, 290). While in a sent response to UNESCO writes: “Applied science in the service, first, of big business and then of government has made possible the modern totalitarian state”. For this reason, as for many other, makes a call for a new Manhattan Project, of which he thought should benefit the vast majority of people, not only centralized powers with the ruling elite (Aldous Huxley, June 1947).

Like in a dialectical movement of history, the answer to the national-socialism of last century could be a global ideology, no less harmless and radical than those were before, by having the same devastating effects. In one of his last public apparitions, Huxley warned us that under the pressure of some impersonal forces, like the population growing and ending of natural resources, or over- organization and technological progress, these might lead to decentralization of the governments’ power. And to the concentration of her into the hands of a small group of people, namely of an oligarchy, which will lead us towards a world dictatorship, not only in the United States (The Mike Wallace Interview, 1958).

‘Brave New World’ seen through the eyes of Aldous Huxley

The East and West have known their titans in the First and Second World War, but America had her own Gods too. By the ’20s, Henry Ford, one of the richest men in the world, was seen as a visionary inside and outside of America. Ford was the America’s God.

His project ‘Fordlandia’ had as purpose cultivating a rubber plantation in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon for developing his cars businesses. Also, building up a whole city, a miniature Midwest factory town. The exportation of the American way of life in the jungle of Amazonia. It was envisioned to go so far until at regulating even the smallest aspects of employees’ private life. Almost like in a totalitarian society remarks the writer and history professor, Greg Grandin, in a televised interview (Greg Grandin).

Wonder if his project of building up from foundations a whole city, a civilized world in the jungle, ruled by a Corporation and its economic laws, still exists today?

What else inspires Huxley’s fable is a “visit to the Billingham Manufacturing Plant, a large chemical processing plant run by industrialist Alfred Mond” (COVE Editions). Baron Mond and Henry Ford are two key characters in his tale. Could Huxley have been inspired by both this visit and the Ford’s project? We don’t know for sure, but the society described in Brave New World resembles in many ways with Ford’s dreamed society.

In Brave New World, the action starts at the Central London Hatchery and Conditioning Centre, which is under the ‘Surveillance eye’ of the World State, as the slogan displayed at the entrance of this grey building of only thirty-four stories shows: Community. Identity. Stability.

Unfortunately, Huxley doesn’t tell us too much about how this World State’s governance functions outside of London. He speaks only of an advanced technological society from a distant future, year 632 A.F. (2540 after Ford). Ruled by the principles of scientific research, technological progress, and of the market economics’ laws. And in which doesn’t exist anymore elected presidents, neither states’ suzerainty. Only ten World Controllers, what it means that the World State is divided into ten regions with their centralized power, most probably, in the City of London. Mustapha Mond (alias, the Baron Alfred Mond in real-life) is the Resident World Controller for Western Europe. Huxley’s whole new world offers us the picture of a global community where businessmen as Alfred Mond and Henry Ford are deified.

In this advanced society, there are flying machines in the sky. The passing from a geographic area to another takes place with helicopters and rockets. No single trace from the old way of traveling. Driven cars on the asphalt, bedtime stories. Children no longer are conceived by natural birth but in artificial wombs. Viviparous reproduction, marriage, seen as something obscene. London Hatchery and Conditioning Centre it’s such a place where children are artificially born and conditioned from birth to death to be ‘happy’ in the caste they belong to Alphas, Betas, Gammas, and so on.

Outside, at the margins of civilization, are natural reservations inhabited by savages like New Mexico Reservation. Babies still are born in a natural way there. Their small and poor community keeps the old traditions related to religion and marriage. Things that in the civilized world are completely abolished, erased from the collective memory. Just like history with all her past that stood behind.

‘History is bunk’ in this new world, says Mond to a group of students. All the history, together with his inherited wisdom, from Gautama Buddha to Homer, and Jesus, is swept. Old literature, whisks. Shakespeare, all the poetry prohibited. Passed to Index Librorum Prohibitorum. So the Bible. It’s a prohibited book, hidden in a large safe by the World Controller for Western Europe. The only book that is left free to circulate is Ford’s ‘Bible’, the biography about his life and his work, published for spreading the Fordian knowledge in the new world (Aldous Huxley,2011, 92, 250, 262. See also the English edition, 2005).

“In the novel, all religion has faded away and been forgotten by the citizens of the World State. The only deity-like or religious principles that people follow are that of Henry Ford, inventor of the Model T” (Derek D. Miller). When Ford introduced his Model T automobile on market, this revolutionized transportation and American industry. ‘Fordism’, with his global vision for a stable society, where the productivity of inexpensive goods and the consumption of them offers a higher standard of life, puts an end to social conflicts, so it’s the key to peace and happiness, has become America’s new religion soon after the end of WWI. Quite similar, Huxley imagines a technologically advanced society, with flying machines, in which the inventor and his inventions are deified by the modern masses.

In the words of Neil Postman, this would be a ‘technopoly’, or a ‘totalitarian technocracy’ where all the cultural forms of life, art, religion, even the science, are sacrificed on the altar of technological progress, for illusory happiness. Thus, people no longer are the children of the real God, not even citizens of the world, just mere consumers.

Instead of conclusions. Do we live in Huxley’s Brave New World?

Is this picture of Model T society cut out from a science-fiction film? Maybe Ford’s project and Huxley’s imagined society, with his city from the future, is much closer to us than we ever thought. After all, we live in a consumption society where almost everybody can afford to buy a car as Ford dreamed of. And thanks to the modern assembly line and mass-production, now we have easier access to all cheap goods which are supposed to make us feel ‘happier’. But can happiness be reduced at mere consumption for pleasure? Because this is what we have today: a consumption for pleasure, not only for our needs. We devour the goods that we buy quicker than cannibals. Smash, to the garbage! It’s a cannibalistic behavior, but more it’s self-destructive behavior, of alienation.

Consumption, in any way, is the New World’s religion. Happiness is not anymore a quest for the individual but becomes social happiness, the happiness ‘to go shopping’, how Bush said after 9/11, and perhaps this makes her so illusory. But precisely this was Ford’s dreamed society and of the elite of course. A society where the new generation is neuro-linguistically programmed by the media propaganda (through marketing and rhetoric tricks) to work for the World State, its ruling corporations, and to consume more. Everything becomes surface, but there’s no deep in it.

Buddha would have answered to the irrationality of the (post) modern masses: Stick within the Self, if you don’t want to ruin yourself! The Self, the inner capacity of interrogation and free-thinking, is what any totalitarian government has sought to destroy. That’s why, in 1984 and Brave New World, solitude and true love (not of the Ministry of Love) are condemned. Because by thinking and loving anyone can oppose dictatorship, fact that might put a little bit in danger the hierarchical structure that holds the power. People are kept in an endless parade of distractions in Brave New World so that they never know that has been taken from them their liberty, along with their choices and decisions.

Free entertainment and irrational consumption pursue to distract people’s attention from the process of decisions in which they are not involved anymore as mere consumers. After how they are not involved in searching for the truth, for understanding the reality in which live. Truth becomes irrelevant, feared Huxley. Indeed, “what’s the point of truth or beauty or knowledge when the anthrax bombs are popping all around you?” Everything has started to be controlled since the Nine Years’ War, even people’s desires, the Western Controller says to John the Savage (Aldous Huxley,2011, 260).

We could ask the same if isn’t our world radically changed after the events from 9/11? Don’t we live in a less free world since then? Perhaps Margaret Atwood was right when she suggested that the West comes with its own version of totalitarianism. That we might possibly live in both scripts, of these two parallel worlds, 1984 and Brave New World, at the same time.

The latest technical devices for monitoring private life resemble Big Brother from 1984. Is no longer necessary for a single party with his dictatorial leader to enslave the world, if the World Controllers can do the same job for the World State, by disposing of advanced technology. However unrealistic it might seem Brave New World is not pure fiction. The vision of a world split into ten political/economic regions or kingdoms can be found in the Club of Rome published report from September 17, 1973, called ‘Regionalized and Adaptive Model of the Global World System’ (Pleasanton Weekly). To my mind, I think this vision is much older than that, of whom, most probably Huxley knew.

So, yes, Huxley’s predictions upon our future might be true. We still don’t have ten world’s regions, flying cars, babies born in artificial wombs, but it’s a matter of time. Most recent scientific researches in the medical field related to artificial wombs show that in the proximate future we might have tube babies, fertilized and born outside the maternal womb, how Huxley foresaw (Sahotra Sarkar). The more so as the latest legislation regarding sexual education adopted in Brussels, with its accent put on the autonomy of the human body, encourages this type of research (European Parliament resolution, June 24, 2021).

All of that, together with e-Governance from Estonia, the first smart city from the future, Neom, launched probably before 2050 in the Middle East, or the Space Kingdom of Asgardia, shows that this new world comes upon us, whether we want, or not want, and that might turn overnight into a terrifying nightmare.

References

Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (1932). COVE Editions. Web.

Atwood, Margaret. Margaret Atwood on why we should all read Brave New World. London: Penguin Random House, February 8, 2017. Web.

Ball, Philip. In retrospect: Brave New World. London: Nature 503, 338-339 (2013). Web.

Dacre, James. James Dacre: are we living Brave New World’s nightmare future? London: The Guardian, September 18, 2015. Web.

European Parliament resolution ‘Sexual and reproductive health, and rights in the EU, in the frame of women’s health’. Brussels: June 24, 2021. Web.

Feaver, Peter. Now I remember why President Bush urged people to go about their daily lives. Washington, D.C.: Foreign Policy, 2013. Web.

Grandin, Greg. Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City. New York: Democracy Now, 7/2/09 1 of 2. YouTube. Web.

Huxley, Aldous. The Rights of Man and the Facts of the Human Situation (or ‘Defeating the enemies of freedom’). Paris: UNESCO, June 1947. Web.

Huxley, Aldous. The Ultimate Revolution. USA: Berkeley Language Center, March 20, 1962. Public Intelligence transcript, published on August 12, 2010. Web.

Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World: And, Brave New World Revisited. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2005. Print.

Huxley, Aldous. Minunata lume nouă: Și, Reîntoarcere în minunata lume nouă. Iași: Polirom, 2011. Print.

Keiper, Caitrin. Brave New World at 75. Washington, D.C.: published by The Center for the Study of Technology and Society, The New Atlantis 16, 41-54 (Spring 2007). Web.

Miller, Derek D. Brave New World and the Threat of Technological Growth. USA: Inquiries Journal, 2011. Web.

Pleasanton Weekly. The Truth behind Aids. California: Embarcadero Publishing Company, 2009. Web.

Sarkar, Sahotra. Lab–grown embryos and human–monkey hybrids: Medical marvels or ethical missteps? UK: The Conversation Trust, April 22, 2021. Web.

The Mike Wallace Interview – Aldous Huxley interviewed by Mike Wallace: 1958 (Full). USA: American Broadcasting Company (ABC), September 28, 2011. YouTube. Web.