The Ultimate Revolution and its Brave New World (third part) (English version at the end of this article)

Natura fiecărui război și a oricărei revoluții a fost și este în primul rând ideologică. Celelalte motive, cum ar fi motivele economice prea des invocate, legate de epuizarea resurselor, servesc doar pentru a le justifica.

Dacă luăm de exemplu Revoluția din Octombrie a bolșevicilor sau Revoluția din Noiembrie a Republicii de la Weimar, ne dăm seama că în fundalul lor mereu s-a aflat un punct de vedere ideologic. Bolșevicii vedeau în burghezie (fr. le bourgeoisie) dușmanul de clasă și al poporului, în timp ce naziștii vedeau în evrei dușmanul rasei ariene.

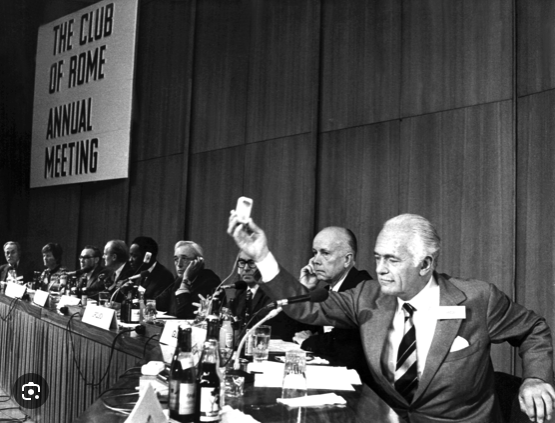

Elita de azi a gătit o nouă ideologie pentru mase, creată în jurul ideii de sat global și apocalipsă a mediului. Astfel a fost declarată o adevărată luptă împotriva sărăciei și a bolilor, având drept scop reducerea populației mondiale printr-o politică de creștere zero ale cărei origini se regăsesc în rapoartele Clubului de la Roma.

Viziunea Clubului de la Roma pentru un guvern mondial

În timpul primului război mondial, mulți credeau că acesta va fi Marele Război care va pune capăt tuturor războaielor. Dar, așa cum ne-a arătat istoria, nu s-a întâmplat. Primul război mondial a fost urmat de al doilea și, chiar dacă se credea din nou că este Marele Război, nu a pus capăt tuturor conflictelor armate care au urmat după ele.

Sub acest spectru, o nouă viziune asupra lumii a început să se contureze. Purtând cu ea ideea unificării tuturor națiunilor în numele păcii, de a construi o lume mai bună de la temelii. Organizații internaționale precum Națiunile Unite și agenția sa specializată Unesco au făcut o pledoarie în acest sens de la început. Unesco Courier menționa într-un număr din aprilie 1949 că trebuie să reconstruim temelia civilizației noastre. La un an după adoptarea Planului Marshall. Idee care se reflectă foarte bine în declarațiile interesante ale politicianului mexican Torres Bodet, totodată cel de-al doilea Director General Unesco la acea vreme:

„Acordăm prioritate maximă proiectelor care sprijină direct planurile U.N. pentru zonele subdezvoltate”. „Sarcina Unesco este de a crea o comunitate mondială, în care indivizii de pretutindeni să simtă că aparțin nu numai unei națiuni, ci sunt și cetățeni ai ceea ce Wendell Willkie numea „o singură lume”…” (vezi Unesco Courier, UNESCO can aid U.N. Plan for under-developed areas, Torres Bodet says, pp. 1-2).

Și continuă prin a ne spune că generațiile viitoare vor suferi de foame și că războaiele vor fi încurajate din pricina epuizării resurselor naturale. Campania UNESCO „Food and People” – un program de educație în masă, desfășurat în parteneriat cu Organizația Națiunilor Unite pentru Alimentație și Agricultură – a fost inițiată pentru a-i face pe oameni să conștientizeze acest lucru.

Întrebându-se dacă vom avea parte de-o mare cruciadă, Torres Bodet nu a negat-o. Mai mult întreabă „de ce națiunile și indivizii nu ar trebui să întreprindă această cruciadă pe timp de pace, așa cum au făcut-o, cu riscul vieții lor, în război?” (Ibid., pp. 3-4)

Nici Aldous Huxley nu părea mai optimist în această chestiune. În articolul său „Double Crisis”, publicat tot în Unesco Courier, el vorbește despre o criză care există pe două niveluri – o criză politică și economică situată la nivel superior și o criză la nivel inferior a populației și a resurselor mondiale. Ceea ce vede majoritatea e doar vârful aisbergului.

Spre deosebire de Aurelio Peccei, care peste ani va vorbi despre sărăcia din mijlocul abundenței, Huxley credea că mai bine am vorbi despre sărăcie în mijlocul sărăciei. Prosperitatea zilelor noastre ar fi consecința nefastă a cheltuirii prea repede a capitalului de neînlocuit de pe această planetă. Ceea ce a provocat eroziunea solului și a făcut ca fertilitatea lui să scadă. Fapt care poate pune capăt oricărei civilizații, plasându-ne în proximitatea unui război perpetuu (vezi Aldous Huxley în Unesco Courier, The Double Crisis, p. 6).

În timp ce reflecțiile lui Peccei au fost puternic influențate de dezbaterile de la sfârșitul anilor ’49 privind dezvoltarea și diviziunea Nord-Sud, Huxley credea într-un fel ca Bodet că foametea ne va afecta pe noi toți.

„În țările dezvoltate problema subdezvoltării se exprimă – într-un climat încă „progresist” la nivel global – în termeni de înapoiere, și mai ales de foamete: problema „foamei în lume” nu a fost niciodată la fel de populară ca în acești ani și a fost sursa a două teorii diferite: una centrată pe retorica „revoluției verzi”, deci pe capacitatea tehnologiei de a eradica năpasta; cealaltă centrată pe imposibilitatea Pământului de a susține o populație în continuă creștere” (Luigi Piccioni).

Toate aceste dezbateri nu au rămas fără ecou în epocă. Au fost de fapt ca o trambulină pentru Revoluția Verde. În Italia ia naștere o mișcare ecologică ducând la apariția mai multor asociații pe probleme de mediu. „Il Gruppo Verde” al Italia Nostra fusese unul dintre cele care fondase în 1966 Apelul Național Italian al World Wildlife Fund (Ibid.). Ulterior, Clubul de la Roma apare trăgând semnale de alarmă prin rapoartele publicate.

„Predicamentul omenirii” de la Geneva (1970)

Clubul de la Roma avea afinități puternice cu Societatea Lunară din Birmingham, dar și cu „futuribilii” lui Bertrand de Jouvenel. Aidoma lor, ei au publicat multe studii speculative care prognozează viitorul. Nu e de mirare că Jouvenel a fost cooptat în Club. A fost unul dintre cei care a simpatizat cu viziunea lui Aurelio Peccei încă de la înființare.

Bertrand de Jouvenel a participat la întâlnirea care a avut loc în septembrie 1968 la Accademia dei Lincei din Roma. Alături de alte treizeci de figuri notabile, cum ar fi fizicianul Premiului Nobel Dennis Gabor sau Hugo Thiemann, directorul Institutului Battelle din Geneva. Fondarea Clubului se datorează acestei întâlniri și uneia mult mai devreme din aprilie convocată de Accademia dei Lincei și Fundația Agnelli. Poate și datorită „Conferinței privind condițiile ordinii mondiale” de la Bellagio (vezi Alexander King în Club of Rome, DOSSIERS 1965-1984: THE LAUNCH OF A CLUB, la HYPERLINK „http://clubofrome.fi/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Dossiers.pdf” http://clubofrome.fi/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Dossiers.pdf).

Data înființării sale se află în umbră însă. Singura dată oficială pe care am găsit-o este martie 1970: „Clubul de la Roma a fost fondat în martie 1970 la Geneva ca o asociație privată non-profit potrivit Codului Civil Elvețian. Secretariatul său se află la Roma; iar filialele sau birourile vor fi stabilite în diverse părți ale lumii, primele două fiind la Geneva, Institutul Battelle, și-n Tokyo, la Japan Techno-Economics Society” (cf. Anexei I din The Predicament of Mankind, 13 martie 1970).

Trei persoane au fost fundamentale în modul de gândire și calea de viață a lui Aurelio Peccei: Julian Huxley, Alexander King și Eleonora Barbieri Masini (vezi Carolina Facioni). Întreaga sa viziune asupra lumii va fi rezumată în această propunere de proiect de prin anii ’70, intitulată pe scurt Predicamentul omenirii („The Predicament of Mankind”). Astfel, „Predicamentul” este unul dintre primele documente oficiale ale Clubului de la Roma, avându-i drept autori pe Hasan Özbekhan, Erich Jantsch și Alexander Christakis. Peccei s-a bucurat și de sprijinul lui Hugo Thiemann în acei ani, prin intermediul căruia Institutul Battelle a oferit cadrul administrativ pentru dezvoltarea proiectului (The Predicament of Mankind, p. 30).

Deși începuturile au fost în metalurgie și-n cercetarea combustibililor, activitățile sale s-au extins în toate domeniile tehnologiei, menționa Frank C. Croxton, Directorul Adjunct al Institutului Battelle într-o publicație a vremii. Mai mult, el ne spune că Laboratorul Battelle de la Geneva este „unul dintre cele trei care, cu o stație de cercetare marină în Florida, constituie facilitățile experimentale ale Institutului” (Frank C. Croxton).

De ce a fost aleasă această locație pentru derularea proiectului și nu o alta? Nu știm. Așa cum nu știm numele celor care au format Comitetul Executiv în 1970. Numele lor nu sunt menționate nici măcar în anexele de la sfârșit. Au rămas ascunse în umbră întocmai ca data înființării clubului.

Ceea ce știm este că acest proiect al Clubului de la Roma a apărut în ’70 cu o „viziune proaspătă” pentru implementarea unei „ordini umane cu totul noi”. Viziunea plutea oricum în aer după Conferința de la Bellagio din ’65 și adoptarea Planului Marshall pentru Europa. Dar această ordine umană cu totul nouă nu va fi atât de sfântă precum vom vedea („but this wholly new human order will not be so holy”).

În câteva rânduri, viziunea proiectului a fost conturată în jurul termenului de problematică și a echilibrului ecologic bazat pe valori. Potrivit autorilor săi, „problematique” înseamnă o meta-problemă generalizată (sau un meta-sistem de probleme) care s-a multiplicatla nivel mondial în probleme critice continue, cum ar fi suprapopularea, malnutriția, sărăcia, poluarea etc. Ele fiind menționate de către autori într-o listă ilustrativă foarte lungă de 49 de probleme (The Predicament of Mankind, pp. 14-16).

Pentru restabilirea echilibrului mondial, inițiatorii proiectului au atras atenția celor din autoritatea publică și au convins guvernele să tragă linii noi în politică. Acest lucru a mers „atât de departe, încât s-a stabilit o serie de contacte cu oameni cheie din Ottawa, Moscova, Washington, Tokyo, Buenos Aires, Stockholm, Berna, Viena și alte capitale ale lumii, precum și-n organizații internaționale” (Ibid., pp. 9-10. Vezi și Anexa I).

Un alt exemplu îl oferă convocarea unui Forum Mondial creat de guvernele țărilor industrializate printr-un act de voință politică care va încuraja un dialog asupra constatărilor proiectului (vezi al cincilea obiectiv al proiectului de la pagina 10. De asemenea, Anexa II: Ideea unui forum mondial, pp. 32-34). Cât și de organismele la nivel internațional NATO și OCDE care deja și-au asumat unele sarcini în această direcție. Sau de Conferința ONU asupra mediului uman care în ’70 se afla pe drum spre Stockholm, adică în curs de desfășurare.

Predicamentul sună destul de minunat de citit, cu atât mai mult cu cât în aproape toate documentele oficiale, Clubul Romei pretinde a fi apolitic și fără nicio implicație ideologică, dar oare chiar așa este și a fost de la bun început? Singurul Forum Mondial care apare în Cantonul Genevei, la un an după ce propunerea a fost înaintată guvernelor prin intermediul acestui proiect de cercetare, este Forumul European de Management, cunoscut astăzi ca Forumul Economic Mondial (WEF) al lui Klaus Schwab.

Poate datorită acestei bucăți de istorie și a unor obiective comune, Forumul Economic Mondial (WEF) a avut câțiva invitați speciali în 2020 din partea Clubului de la Roma la reuniunea lor anuală din Alpi (Wikipedia, World Economic Forum. De asemenea, vezi Fred Donaldson, Why was the Club of Rome invited to attend the W.E.F. in Davos?).

Cartea „Limitele creșterii” (1972)

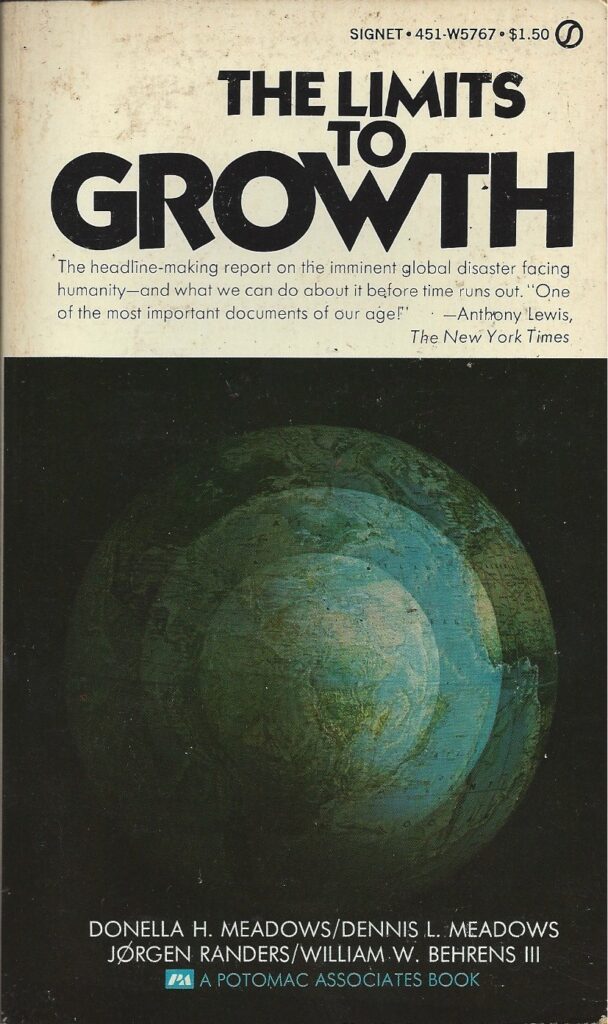

1972 e un an important de amintit cel puțin pentru două evenimente majore: Cartea „Limitele creșterii” și Conferința de la Stockholm. Când „Limitele” a fost publicată pentru prima dată pe 2 martie, a fost un succes real, chiar mult mai bine primită de public decât Brave New World a lui Aldous Huxley. „S-a vândut în 12 milioane de exemplare în 37 de limbi” (Keith Suter). O previzualizare a apărut într-un număr al revistei Futuribili din aprilie ’71 (revista lui Bertrand de Jouvenel și a Fundației Ford), care de atunci a publicat multe puncte de vedere diferite, dar în general simpatice cu teza explicată în „Limitele” (Luigi Piccioni. Vezi și The Futurists (1967) | Scientists Predict The 21st Century, postat pe YouTube, 15 dec 2018).

Cartea a fost transformată într-un eveniment de o zi găzduit de Centrul Woodrow Wilson din Washington, ne spune fizicianul american Philip H. Abelson în Science Review:

„Publicul și liderii săi sunt acum conștienți și îngrijorați pe bună dreptate de potențialele consecințe neplăcute ale creșterii excesive. Nu e de mirare, așadar, că un simpozion de-o zi privind „Limitele creșterii” organizat la Centrul Woodrow Wilson din Washington pe 2 martie a trebuit să atragă o audiență atentă, care a inclus senatori, ambasadori și un ofițer de cabinet, precum și numeroși reprezentanți ai presei, radioului și televiziunii” (Philip H. Abelson).

Dennis Meadows, unul dintre autorii cărții, a fost principalul orator al evenimentului. „The Limits” a prezentat rezultatele unui grup de cercetare condus de el la Institutul de Tehnologie din Massachusetts. Soția sa, Donella H. Meadows, a fost co-autor. Un studiu conceput ca un raport special pentru proiectul Clubului de la Roma privind „Predicamentul omenirii”.

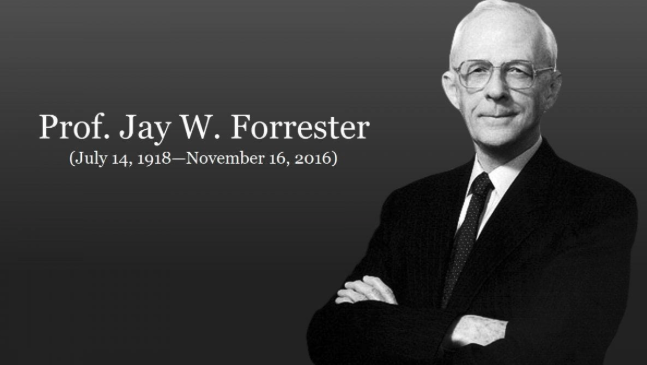

Potrivit lui William Watts, președintele editurii Potomac Associates, prima etapă a studiului a luat o formă clară în timpul întâlnirilor desfășurate în vara anilor ’70 la Berna, Elveția și Cambridge, Massachusetts. La o conferință de două săptămâni la Cambridge, profesorul Jay Forrester de la Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), a oferit un model global și chiar a sugerat o tehnică, o nouă metodă (numită „World Dynamics”) pentru a analiza problematica lumii (vezi Predicamentul omenirii. Faza I: Dinamica echilibrului global, la HYPERLINK „https://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/190536” https://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/190536).

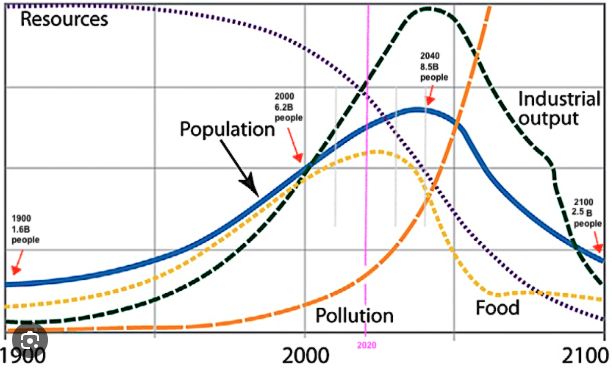

Echipa internațională a domnului Meadows a examinat cinci factori de bază care au determinat creșterea exponențială pe această planetă, dar și au limitat-o. Aceste variabile au fost introduse într-un model computerizat World3 pentru a simula consecințele interacțiunilor dintre Pământ și sistemele umane. Așadar, am putea spune că cercetarea a vizat mai curând populația lumii a treia. Sau, în cuvintele domnului Watts, a studiat „sărăcia din mijlocul abundenței”. Menționăm aici că acest lucru nu ar fi fost posibil fără sprijinul financiar al Fundației Volkswagen (vezi Prefața lui William Watts, în The Limits to Growth, p. 11. De asemenea Wikipedia, The Limits to Growth).

Termenul de „creștere exponențială” a fost preluat din matematică și desemnează un fenomen foarte dinamic, implicând elemente care se schimbă în timp. În studiu, găsim doar cinci elemente de bază analizate așa cum am menționat mai sus, precum populația, producția de alimente, industrializarea, poluarea și consumul de resurse naturale neregenerabile, elemente care interacționează între ele provocând creșterea.

Concluziile studiului sunt destul de sumbre în acest sens. Dacă tendințele actuale de creștere nu se vor schimba, atunci planeta își va atinge limitele în următorii o sută de ani. „Până în anul 2050, mai multe minerale ar putea fi epuizate dacă ritmul actual de consum continuă”, se arată în raport (vezi Donella H. și Dennis L. Meadows, The Limits to growth, pp. 23-25, 31, 55. De asemenea, ABC News, Computer predicts the end of civilization (1973)|RetroFocus, pe YouTube).

„The Limits to Growth” a fost, fără îndoială, un mare eveniment care a creat un adevărat fenomen în lume, la fel ca Revoluția Verde. Dar, în ciuda impactului său, cartea a primit multe critici.

New York Times, una dintre cele mai vehemente voci ale vremii, declara că „este o lucrare goală și înșelătoare”. Care folosește tehnica simulării matematice pentru a prezice viitorul. Prin dispozitive moderne, un aparat impunător al tehnologiei informatice și jargonul sistemelor, preia presupuneri arbitrare pentru a ajunge la concluzii arbitrare pretizând că sunt științifice și adevărate (vezi The New York Times, The Limits to Growth, 2 aprilie 1972).

Contrar a ceea ce susțineau autorii, tehnica nu este nouă. Modelele de simulare au fost folosite cu mult înainte pentru a testa proiectele de inginerie la costuri reduse, în domeniile economiei și sociologiei. Problema cu The Limits este că face predicții prea îndepărtate, până la ani-lumină, pentru secole; iar viziunea sa se extinde peste întreaga lume, învingând eroic orice studiu de inginerie sau economie de până-n prezent. O simulare însă este doar un viitor posibil și nu viitorul. Asta înseamnă că o eroare se poate strecura cu ușurință în orice scenariu de predicție. Mai ales când se bazează pe câteva variabile de calcul și predicțiile merg atât de departe în timp.

După cum arăta articolul din The New York Times, rezultatele în orice simulare depind în mare măsură de informațiile care alimentează computerul. Dacă datele introduse se referă doar la creșterea populației, producția de alimente, consumul și efectele sale secundare, cum ar fi poluarea sau sărăcia, atunci nu este surprinzător faptul că simulările bazate pe „modelul mondial” al lui Meadows și Forrester se termină inevitabil în colaps.

Jay Forrester a avut și o încercare anterioară de a prezice viitorul, mult mai optimistă, prin „Dinamica Urbană”. Dar fie că luăm ca exemplu „Dinamica urbană” sau „Dinamica lumii”, ambele prezintă o divizare, fragmentare în interiorul orașelor (sau în lume) între zonele cele mai bogate și cele mai sărace. Astfel încât putem spune că modelul său mondial (global) anticipează destul de bine viitoarele orașe inteligente de mâine, înconjurate de zone sălbatice, așa cum apare descris în fabula lui Huxley, Brave New World, sau cum s-a văzut în distopia lui Andrew Niccol, In Time.

„Încercarea lui Forrester de a prezice viitorul lumii prin simulare pe computer are precedent în încercarea sa anterioară de a prezice viitorul orașelor. Abordarea lui „Urban Dynamics” este în mod substanțial aceeași cu „World Dynamics”. Mai degrabă sunt create ecuații motivate pur și simplu ca indicatori pentru forțele care modelează structura economică a zonelor urbane. Simularea permite apoi analistului să extrapoleze trecutul și prezentul în viitor” (Ibid.).

Așa cum „World Dynamics” oferă o justificare computerizată pentru încetarea creșterii printr-un model global virtual, futurist, conceput mai ales pentru populația Lumii a Treia, „Urban Dynamics” oferă o justificare pentru ceea ce se consideră a fi neglijare benignă, ne spune rubrica din ziar. Cu alte cuvinte, ambele modele oferă o justificare electronică pentru o lume sau un oraș în care săracii nu mai au unde să trăiască. Întrebarea este dacă această viziune se află în afara oricărei ideologii. Întrucât dacă ne gândim la politica de creștere zero pe care o promovează, ne dăm seama că nu e atât de pură, lipsită de orice conținut ideologic. Domnul Meadows și domnul Forrester au fost poate prea grăbiți cu presupunerile lor cu privire la creșterea exponențială, la fel cum a făcut-o reverendul Thomas Malthus cu secole în urmă.

„Planeta are cu siguranță problemele ei – și poate chiar o „problematică” sau două”. Dar a crea un scenariu apocaliptic al mediului, la modă în zilele noastre, este puțin prea mult pentru oricine nu și-a pierdut simțul comun. Lupul care plânge e într-adevăr o funcție prea importantă pentru a fi lăsată doar pe seama colegiilor invizibile, așa cum conchide articolul.

Numele celor care au constituit Comitetul Executiv apare în cartea Limitele creșterii (din martie 1972), care este un raport pentru proiectul Clubului de la Roma privind „Predicamentul omenirii”.

Aurelio Peccei a fost „prima forță de mișcare din cadrul grupului. Alți lideri ai Clubului de la Roma îi includ pe: Hugo Thiemann, șeful Institutului Battelle din Geneva; Alexander King, director științific al Organizației pentru Cooperare și Dezvoltare Economică; Saburo Okita, șeful Centrului Japonez de Cercetare Economică din Tokyo; Eduard Pestel de la Universitatea Tehnică din Hanovra, Germania; și Carroll Wilson de la Institutul de Tehnologie din Massachusetts”.

În această direcție, vezi Donella H. and Dennis L. Meadows, The Limits to growth: Foreword, pp. 9-10.

Ana-Maria Caminski

Corespondent in Romania, pentru NASUL TV Canada

The Ultimate Revolution and its Brave New World (third part)

The nature of every war and any revolution was and is primarily ideological. The other reasons, such as the economic reasons too often invocated, related to resource depletion, serve only to justify them.

If we take for example the October Revolution of the Bolsheviks or the November Revolution of the Weimar Republic, we realize that in their background there was always an ideological point of view. The Bolsheviks saw in the bourgeoisie the enemy of class and people, while the Nazis saw in the Jews the enemy of the Aryan race.

Today’s elite have cooked up a new ideology for the masses, coined around the idea of the global village and environmental apocalypse. Thus a real fight against poverty and disease was declared, having as a purpose the reduction of the world’s population through a zero growth policy whose origins can be found in the Reports of the Club of Rome.

Club of Rome’s vision for a world government

During World War I, many believed that this would be the Great War that would end all wars. But, as history has shown us, it did not happen. The First World War was followed by the Second, and even if it was thought to be the Great War once again, it did not end all the armed conflicts that followed them.

Under this specter, a new worldview began to take shape. Carrying with it the idea of unifying all nations in the name of peace, to build up a better world from its foundations. International organizations like the United Nations and its specialized agency Unesco made a plea for this from the beginning. Unesco Courier magazine mentioned in an April 1949 issue that we must rebuild the foundation of our civilization. A year after the Marshall Plan was adopted. The idea is reflected very well in the interesting statements of Mexican politician Torres Bodet, also the 2nd Director-General of Unesco at that time:

“We are giving top priority to projects which directly support the United Nations plans for underdeveloped areas”. “The Job of Unesco is to create a world community, in which private individuals everywhere feel that they belong not only to a nation but are also citizens of what Wendell Wilkie called ‘One World’… ” (see Unesco Courier, UNESCO can aid U.N. Plan for under-developed areas, Torres Bodet says, pp. 1-2).

And continues by telling us that future generations are going to starve and wars will be encouraged due to the ending of natural resources. Unesco campaign’s ‘Food and People’ – a programme of mass education, conducted in partnership with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization – was initiated to make people aware of this.

Wondering if we would have a great crusade, Torres Bodet did not deny it. Furthermore, asks “why should the nations and individuals not undertake this crusade in peace, as they did, at the risk of their lives, in war?” (Ibid., pp. 3-4)

Neither Aldous Huxley seemed more optimistic in this matter. In his column ‘Double Crisis’, also published in Unesco Courier, he speaks about a crisis that exists on two levels ‒ an upper-level political and economic crisis and a lower-level crisis in population and world resources. What the majority sees is only the peak of the iceberg.

Unlike Aurelio Peccei, who years from now will talk about poverty in the midst of plenty, Huxley believed that we better speak on poverty in the midst of poverty. The prosperity of nowadays would be the unfortunate consequence of spending too quickly the irreplaceable capital from this planet. Which has caused soil erosion and made his fertility decline. A fact that can end any civilization, placing us in the proximity of a perpetual war (see Aldous Huxley in Unesco Courier, The Double Crisis, p. 6).

While Peccei’s reflections were strongly influenced by the late ’49s debates on development and the North-South divide, Huxley thought in a way as Bodet did that famine would affect us all.

“In the developed countries the issue of underdevelopment is expressed – in a still globally ‘progressive’ climate – in terms of backwardness, and especially of hunger: the issue of ‘world hunger’ was never as popular as in these years, and it was the source of two differing theories: one centered on the rhetoric of the ‘green revolution’, thus on the capacity of technology to eradicate the scourge; the other centered on the impossibility of the Earth to sustain a constantly growing population” (Luigi Piccioni).

All these debates have not remained without an echo in the epoch. They were actually like a springboard for the Green Revolution. In Italy, an ecological movement was born that led to the emergence of several associations on environmental issues. ‘Il Gruppo Verde’ of Italia Nostra had been one of the founders in 1966 of the Italian National Appeal of the World Wildlife Fund (Ibid.). Later, the Club of Rome appeared pulling alarm signals through published reports.

‘The Predicament of Mankind’ of Geneva (1970)

The Club of Rome had strong affinities with Birmingham’s Lunar Society, but also with the ‘futuribles’ of Bertrand de Jouvenel. Alike them, they have published many speculative studies forecasting the future. No wonder then that Jouvenel was co-opted into the Club. He was one of those who sympathized with Aurelio Peccei’s vision since it was established.

Bertrand de Jouvenel attended the meeting that took place in September 1968 at the Accademia dei Lincei from Rome. Alongside some other thirty notable figures, such as the Nobel Prize physicist Dennis Gabor or Hugo Thiemann, the Director of the Battelle Institute of Geneva. The Club’s founding is due to this meeting and to a much earlier one from April convocated by the Accademia dei Lincei and Agnelli Foundation. Perhaps also due to the ‘Conference on Conditions of World Order’ of Bellagio (see Alexander King in the Club of Rome, DOSSIERS 1965-1984: THE LAUNCH OF A CLUB, on HYPERLINK „http://clubofrome.fi/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Dossiers.pdf” http://clubofrome.fi/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Dossiers.pdf).

However, the date of its founding lies in the shadows. The only official date I have found is March 1970: “The Club of Rome was incorporated on March 1970 in Geneva as a non-profit private association under the Swiss Civil Code. Its Secretariat is in Rome; and representatives or offices will be established in various parts of the world, the first two being in Geneva c/o the Institut Battelle and in Tokyo c/o the Japan Techno-Economics Society” (cf. the Annex I from The Predicament of Mankind, March 13, 1970).

Three persons were fundamental in Aurelio Peccei’s way of thinking and life path: Julian Huxley, Alexander King, and Eleonora Barbieri Masini (see Carolina Facioni). His entire worldview will be summed up in this ’70s project proposal, briefly entitled The Predicament of Mankind. Thus, the ‘Predicament’ is one of the Club of Rome’s first official documents, with Hasan Özbekhan, Erich Jantsch, and Alexander Christakis as authors. Peccei also enjoyed Hugo Thiemann’s support during those times, by which the Battelle Institute provided the administrative framework for the project’s development (The Predicament of Mankind, p. 30).

Although its beginnings were in metallurgy and fuel research, its activities have expanded to all fields of technology, mentioned Frank C. Croxton, the Assistant Director of Battelle Institute in a publication of the time. Moreover, he tells us that the Battelle Laboratory at Geneva is “one of three which, with a marine research station in Florida, constitute the Institute’s experimental facilities” (Frank C. Croxton).

Why was this location chosen for the project’s development and not another one? We do not know. Just as we do not know the names of those who formed the Executive Committee in 1970. Their names are not even mentioned in the Appendices at the end. They remained hidden in the shadows just like the date of the Club’s founding.

What we do know is that this Club of Rome project emerged in the ’70s with a ‘fresh vision’ for implementing a ‘wholly new human order’. The vision was floating in the air anyhow after the Bellagio Conference from the ’65s and the adoption of the Marshall Plan for Europe. But this wholly new human order will not be so holy as we shall see.

In a few lines, the Project’s vision was drawn around the term problematique and the value-based ecological balance. According to its authors, ‘problematique’ means a generalized meta-problem (or a meta-system of problems) that has multiplied worldwide into Continuous Critical Problems, such as overpopulation, malnutrition, poverty, pollution, etc. All of them are mentioned by the authors in a very long illustrative list of 49 issues (The Predicament of Mankind, pp. 14-16).

To restore world equilibrium, the initiators of the project have drawn the attention of those in public authority and persuaded the governments to draw new lines in politics. This went “so far, it has established a number of contacts with key people in Ottawa, Moscow, Washington, Tokyo, Buenos Aires, Stockholm, Berne, Vienna, and other capitals, as well as in international organizations” (Ibid., pp. 9-10. Also see the Annex I).

Another example is offered by the convocation of a World Forum created by the governments of industrialized countries through an act of political will encouraging a dialogue on the project’s findings (see the fifth objective of the project from page 10. Also, the Annex II: The idea of a World Forum, pp. 32-34). As well as the bodies at the international level, NATO and OECD, which have already assumed some tasks in this direction. Or the UN Conference on the Human Environment that in the ’70s was still on its way to Stockholm, i.e. ongoing.

The Predicament sounds quite wonderful to read, the more so as in almost all their official documents, the Club of Rome claims to be non-political and without any ideological implication, but is it really like this and has been from the beginning? The only World Forum that appears in the Canton of Geneva, a year after the proposal was submitted to governments through this research project, is the European Management Forum, today known as the World Economic Forum (WEF) of Klaus Schwab.

Maybe due to this piece of history and some shared goals, the World Economic Forum (WEF) had a few special guests in 2020 from the Club of Rome at their annual reunion in the Alps (Wikipedia, World Economic Forum. Also, see Fred Donaldson, Why was the Club of Rome invited to attend the W.E.F. in Davos?).

‘The Limits to Growth’ book (1972)

1972 is a year important to recall at least for two major events: ‘The Limits to Growth’ Book and the Stockholm Conference. When ‘The Limits’ was first published on March 2, it was a real success, even much better received by the public than Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. “It sold twelve million copies in 37 languages” (Keith Suter). A preview appeared in an issue of Futuribili from April ’71 (the review of Bertrand de Jouvenel and Ford Foundation), which ever since then published many different points of view, but generally sympathetic to the thesis explained in ‘The Limits’ (Luigi Piccioni. Also see The Futurists (1967) | Scientists Predict The 21st Century, posted on YouTube, Dec 15, 2018).

The book was transformed into a 1-day event hosted by the Woodrow Wilson Center from Washington, tells us the American physicist Philip H. Abelson in Science Review:

“The public and its leaders are now aware of and rightly concerned about the unpleasant potential consequences of over-exuberant growth. Small wonder, then, that a 1-day symposium on the ‘Limits to Growth’ held at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington on 2 March should draw an attentive audience that included senators, ambassadors, and a cabinet officer, as well as numerous representatives of the press, radio, and television” (Philip H. Abelson).

Dennis Meadows, one of the book’s authors, was the principal speaker of the event. ‘The Limits’ presented the results of a research group headed by him at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His wife, Donella H. Meadows, was co-authoring. A study designed as a particular report for the Club of Rome project on ‘The Predicament of Mankind’.

According to William Watts, the President of Potomac Associates publisher, phase one of the study took a definite shape during the meetings held in the summer of ’70s in Bern, Switzerland, and Cambridge, Massachusetts. At a two-week conference in Cambridge, Professor Jay Forrester of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), offered a global model and even suggested a technique, a new method (called ‘World Dynamics’) to analyze the world’s problematique (see The preliminary draft of the Predicament of Mankind. Phase One: Dynamics of Global Equilibrium, at HYPERLINK „https://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/190536” https://dome.mit.edu/handle/1721.3/190536).

The international team of Mr. Meadows examined five basic factors that have determined the exponential growth of this planet but also limited it. These variables were introduced in a World3 computer model to simulate the consequence of interactions between the Earth and human systems. So, we could say that the research aimed World3 population rather. Or, in the words of Mr. Watts, studied ‘poverty in the midst of plenty’. We mention here that this wouldn’t have been possible without the financial support from the Volkswagen Foundation (see the Foreword of William Watts, in The Limits to Growth, p. 11. Also Wikipedia, The Limits to Growth).

The term ‘exponential growth’ has been taken from mathematics and designates a very dynamic phenomenon, involving elements that change over time. In the study, we find only five basic elements analyzed as I mentioned above, such as population, food production, industrialization, pollution, and consumption of nonrenewable natural resources, elements that interact with each other causing the increase.

The conclusions of the study are quite gloomy regarding this. If these present growth trends do not change, then the planet will reach its limits within the next one hundred years. “By the year 2050, several more minerals may be exhausted if the current rate of consumption continues”, it tells the report (Donella H. and Dennis L. Meadows, The Limits to growth, pp. 23-25, 31, 55. Also, see the ABC News, Computer predicts the end of civilization (1973) | RetroFocus, on YouTube).

‘The Limits to Growth’ was undoubtedly a great event that created a real phenomenon in the world, just like the Green Revolution. But despite its impact, the book received many critics.

The New York Times, one of the most vehement voices of the time stated that it ‘is an empty and misleading work’. It makes use of the technique of mathematical simulation to predict the future. Through modern devices, an imposing apparatus of computer technology, and systems jargon, takes arbitrary assumptions to arrive at arbitrary conclusions claiming them to be scientifically and true (see The New York Times, The Limits to Growth, April 2, 1972).

Contrary to what the authors argued, the technique is not new. Simulation models were used long before to test engineering designs at low costs, in the fields of economics and sociology. The problem with The Limits is that it makes predictions too far away, up to light-years, for centuries; and his vision expands over the whole world, beating heroically any engineering or economic study to date. But a simulation is only a possible future and not the future. That means an error can easily slip into any prediction scenario. Especially when is based on a few computational variables and the predictions go so far in time.

As the column from The New York Times showed, the results in any simulation depend mostly on the information that feds the computer. If the introduced data concerns only population growth, food production, consumption, and its side effects such as pollution or poverty, then there is no surprise that all the simulations based on the Meadows and Forrester ‘world model’ inevitably end in collapse.

Jay Forrester had also an earlier attempt to predict the future, much more optimistic, through ‘Urban Dynamics’. But whether we take ‘Urban Dynamics’ as an example, or ‘World Dynamics’, both present a division, a fragmentation within the cities (or in the world) between the richest and poorest areas. So we can say that his world (global) model anticipates pretty well the future smart cities of tomorrow, surrounded by wild areas, as is described in Huxley’s fable Brave New World or it has been seen in Andrew Niccol’s dystopia In Time.

“Forrester’s attempt to predict the future of the world via computer simulation has precedent in his own earlier attempt to predict the future of the cities. The approach of his ‘Urban Dynamics’ is substantially the same as ‘World Dynamics’. Rather simply motivated equations are created as proxies for the forces that mold the economic structure of urban areas. Simulation then allows the analyst to extrapolate the past and present into the future” (Ibid.).

Just as ‘World Dynamics’ offers a computerized justification for an end to growth through a virtual, futuristic global model designed mostly for the Third World population, ‘Urban Dynamics’ offers a justification for what is considered to be benign neglect, the newspaper column tells us. In other words, both models provide an electronic justification for a world or city where the poor no longer have a place to live. The question is whether this vision is outside any ideology. Because if we think of the zero‐growth policy that is promoted, we realize is not so pure, devoid of any ideological content. Mr. Meadows and Mr. Forrester were perhaps too hasty with their assumptions regarding the exponential growth, just like Rev. Thomas Malthus had centuries ago.

“The planet certainly has its problems – and maybe even a ‘problematique’ or two”. But to create an environmental apocalypse scenario, fashionable these days, is a little bit too much for anyone who hasn’t lost his common sense. Crying wolf is indeed a too-important function to be left only to invisible colleges, as the article concludes.

Endnote

The names of those who constituted the Executive Board appears in The Limits to growth book (from March 1972), which is a report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the ‘Predicament of Mankind’.

Aurelio Peccei was “the prime moving force within the group. Other leaders of The Club of Rome include: Hugo Thiemann, head of the Battelle Institute in Geneva; Alexander King, scientific director of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; Saburo Okita, head of the Japan Economic Research Center in Tokyo; Eduard Pestel of the Technical University of Hannover, Germany; and Carroll Wilson of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology”.

In this direction, see Donella H. and Dennis L. Meadows, The Limits to growth: Foreword, pp. 9-10.

References

ABC News. Computer predicts the end of civilization (1973), Aug 6, 2018. YouTube.

ABC News. Suter, Keith. Fair Warning? The Club of Rome Revisited. Web.

Club of Rome. DOSSIERS 1965-1984. Helsinki: published by the Finnish Association for the Club of Rome, 2005. Edited by Pentti Malaska and Matti Vapaavuori, and authorized by Alexander King. Web, pdf.

Club of Rome. Ozbekhan, Hasan, eds. The Predicament of Mankind: Quest for Structured Responses to Growing World-wide Complexities and Uncertainties – a Proposal. Geneva: edited by the University of Pennsylvania, Management and Behavioral Science Center, March 13, 1970. Web, pdf.

Club of Rome. Meadows, Dennis L. The preliminary draft of the Predicament of Mankind. Phase One: Dynamics of Global Equilibrium. US, Cambridge, Massachusetts: published by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), April 4-6, 1971. Web, pdf.

Club of Rome. Meadows, Donella H. and Dennis L., and others. The Limits to growth: A report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. U.S., New York: published by Universe Books (A Potomac Associates Book), 1972. Web, pdf.

Croxton, Frank C. Geneva Laboratory of the Battelle Memorial Institute. Published by Nature Publishing Group, vol. 175, January 22, 1955. Web, pdf.

Donaldson, Fred. Why was the Club of Rome invited to attend the W.E.F. in Davos?, February 25, 2020. Web.

Facioni, Carolina, and Roberto Paura. Re-discovering Aurelio Peccei’s contribution to Futures Studies. Published online by the European Journal of Futures Research, on April 29, 2022. Web.

Piccioni, Luigi. Forty Years Later. The Reception of the Limits to Growth in Italy, 1971-1974. Published online by the Donella Meadows Project, an Academy for Systems Change project. Web.

Science review. Abelson, Philip H. Limits to Growth. U.S.: published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Volume 175, Issue 4027, March 17, 1972. Web, pdf.

The New York Times. Passell, Peter, Marc Roberts, and Leonard Ross. The Limits to Growth, April 2, 1972. Web.

UNESCO Courier. UNESCO can aid U.N. Plan for under-developed areas, Torres Bodet says. Volume II, No. 3, April 1949. Web, pdf.

UNESCO Courier. Huxley, Aldous. The Double Crisis. Volume II, No. 3, April 1949. Web, pdf.

Wikipedia. The Limits to Growth. Web.

Wikipedia. World Economic Forum. Web.