Quo Vadis, or where are we going with sustainable development? (Third part) (English version at the end of this article)

Când Operațiunea Rhino începuse în Africa, nimeni nu credea că se va transforma într-o revoluție. Deși nu existau semne vizibile ale unor curente revoluționare subterane, mișcarea de conservare a mediului a dus la o Revoluție Verde în Africa, răspândindu-se ulterior în întreaga lume. Una dintre figurile pioniere a fost Dr. Ian Player, fondatorul Wilderness School (cunoscută și sub numele de WILD Foundation), fără de care mișcarea ecologistă nu ar putea fi înțeleasă sau măcar concepută.

Africa a fost un câmp de bătălie timp de secole, încă de pe vremea când Cecil Rhodes râvnea la bogățiile sale. Ideea că omul alb superior, de obicei un magnat, trebuia să vină cu o „administrare mai bună a vieții sălbatice” este la fel de veche ca goana după diamante a lui Rhodes și a Companiei Britanice a Africii de Sud. Totuși, deposedarea totală a resurselor naturale ale Africii este ceva ce nici măcar Rhodes și compania sa nu au realizat în secolul al XIX-lea. Cu toate că visa să anexeze planetele, poate și continentul sălbatic (vezi Wikipedia, Cecil Rhodes).

Contextul Revoluției Verzi

Respectul pentru natură este ceva ce africanii nu au avut de învățat de la alte civilizații. Nicholas Arthur Steele a exprimat destul de bine acest lucru la cel de-al 4-lea World Wilderness Congress:

„Poporul Zulu are o tradiție de înțelegere a naturii. Conștientizarea lor pentru conservare datează din temeliile societății lor. Deoarece trăiau aproape de natură, trăiau în armonie cu ea și se menținea un echilibru între om și mediul său. Dar acest echilibru s-a pierdut odată cu sosirea omului alb cu armele sale, cu nevoia sa de comerț și, în cele din urmă, cu soldații, fermierii și constructorii de orașe. S-au dezvoltat un nou mod de viață, noi priorități și noi probleme” (vezi Nick Steele, KWAZULU—CONSERVATION IN A THIRD WORLD ENVIRONMENT, în For the Conservation of Earth: Proceedings of the 4th World Wilderness Congress, la https://wild.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/For-the-Conservation-of-Earth_Part_1.pdf).

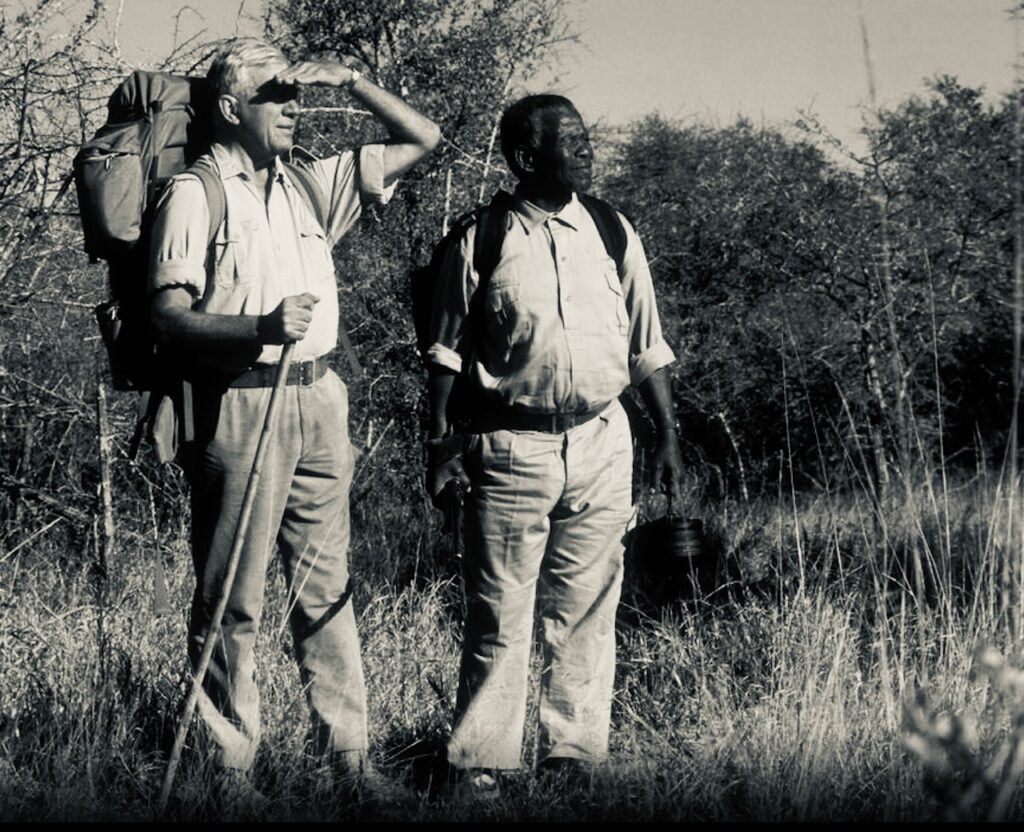

Nick Steele, un activist pentru conservarea naturii și prieten apropiat al lui Ian Player, a fost un alt personaj cheie în Operațiunea Rhino. Alături de mentorul lor Zulu, Magqubu Ntombela, ei s-au aflat în fruntea mișcării de conservare din Africa. Altfel spus, formau fațada vizibilă.

Mișcării i s-au alăturat și personaje mai puțin vizibile. Sir Laurens van der Post, legătura cu altețele regale britanice, împreună cu care Ian Player avea să înființeze primul World Wilderness Congress în 1977 la Johannesburg, jucase la fel rolul unui ghid spiritual, dar mai discret. Am putea spune că el și aristocrația britanică făceau parte din fațada invizibilă. Cu toate că aristocrația britanică și olandeză fusese implicată în politica de conservare a mediului încă de la înființarea World Wildlife Fund (WWF) în 1961. Dar cum a început mișcarea de conservare în Africa? A avut vreo implicație ideologică de la început? (Wikipedia, Laurens van der Post)

Potrivit lucrării de cercetare „Sponsoring nature”, geopolitica din regiunea Africii de Sud din timpul Războiului Rece oferă o platformă utilă pentru interogarea politicii sale de conservare și sponsorizare. În plus, oferă o lentilă utilă prin care putem înțelege rețeaua complexă de relații și interese dintre diferiți actanți răspândiți pe continente, dar uniți de o viziune comună. Viziune care inițial părea preocupată doar de protejarea mediului și care mai apoi apăruse din nevoia (sau, mai degrabă, din teama) de a înfrâna răspândirea comunismului în regiune (Maano Ramutsindela, Marja Spierenburg și Harry Wels, 2011, pp. 45, 49).

Primul fond al Uniunii Internaționale pentru Conservarea Naturii

Wilderness School a fost revoluționară în Africa. Cu toate acestea, viziunea unificatoare asupra lumii nu îi aparținea. Wilderness School (mai târziu WILD Foundation) a urmat o cale similară cu World Wildlife Fund (WWF), și anume, de a strânge fonduri care să extindă semnificativ operațiunile Uniunii Internaționale pentru Conservarea Naturii (IUCN). Împreună, erau ca niște organizații surori unite de o viziune comună într-o caracatiță uriașă:

„World Wildlife Fund (WWF, acum World Wide Fund for Nature) a fost fondată în 1961 cu un singur scop declarat: să strângă bani pentru extinderea drastică a operațiunilor Uniunii Internaționale pentru Conservarea Naturii (IUCN). Înființată la Gland, Elveția, în 1948, pe baza unei constituții redactate de Ministerul de Externe britanic, IUCN se laudă azi cu faptul că este cea mai mare organizație internațională „profesionistă” pentru conservare – din 1994, cuprinzând 68 de state, 103 agenții guvernamentale și peste 640 de organizații non-guvernamentale, „multe cu acoperire globală” ” (EIR, Allen Douglas, 1994).

Un fapt mai puțin cunoscut este că Monarhia Britanică se afla în spatele lor de la început:

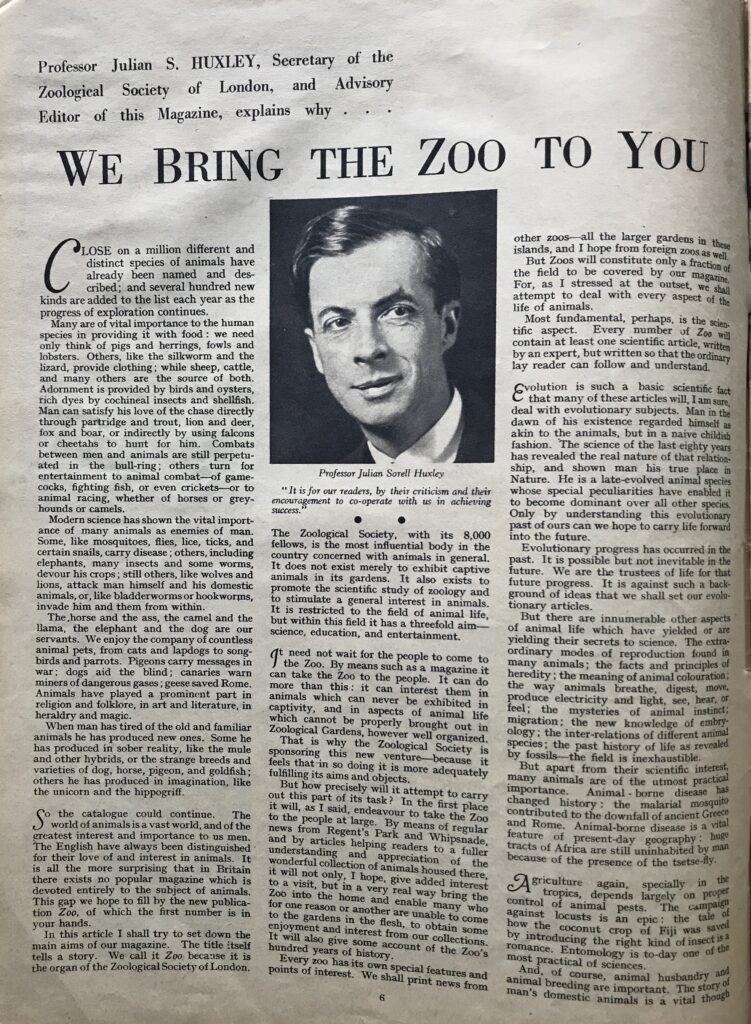

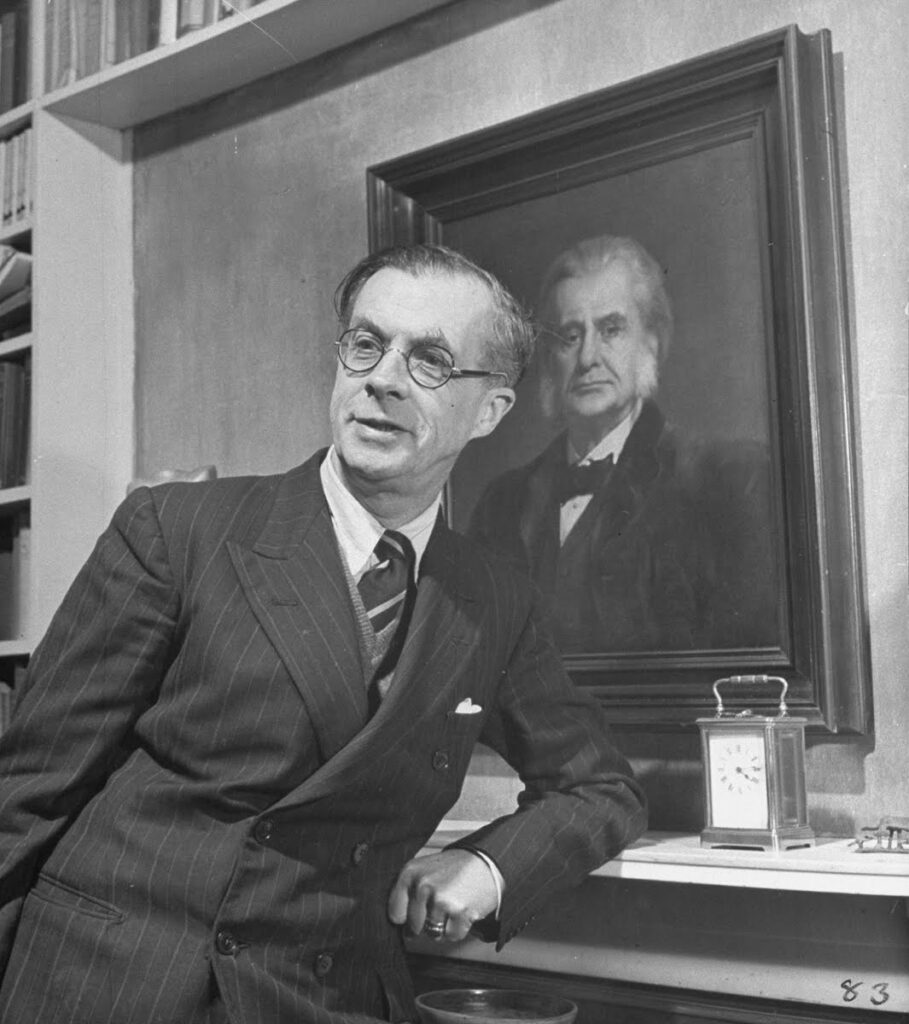

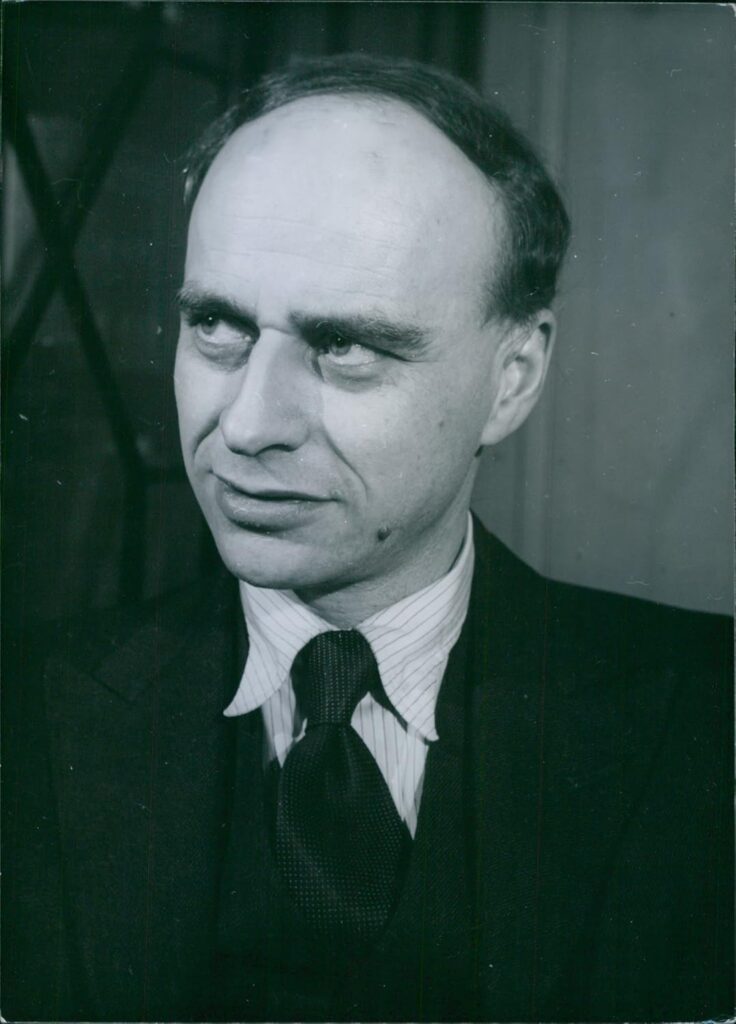

„WWF-IUCN este o filială a două dintre cele mai importante instituții imperiale ale Marii Britanii: Societatea pentru Conservarea Faunei Sălbatice a Imperiului (acum Fauna and Flora Preservation Society, FFPS, al cărei patron este Regina), care a pus bazele parcurilor de vânătoare din întreaga Africă; și Eugenics Society”. „Ceea ce a devenit WWF a prins contur în perioada de dinaintea celui de-al Doilea Război Mondial în cadrul departamentului de Planificare Politică și Economică al unui grup de experți de origine Rhodes al Ministerului de Externe, Institutul Regal pentru Afaceri Internaționale. «Planificarea» s-a concentrat pe eugenie, controlul materiilor prime și guvernarea mondială; cei doi oficiali de rang înalt ai săi, Max Nicholson și Julian Huxley, au fondat ulterior atât IUCN, cât și WWF” (Ibid.).

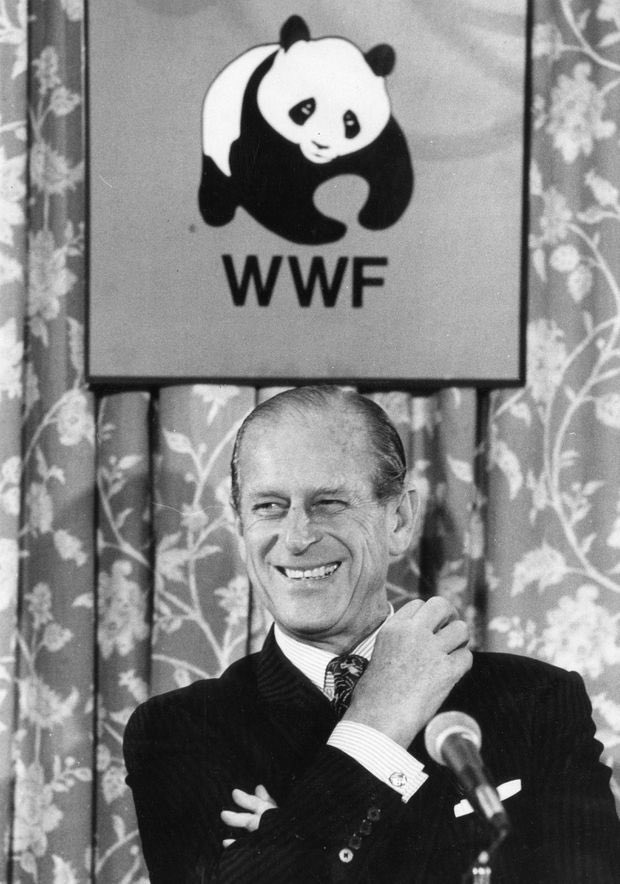

Capetele încoronate, Prințul Philip și Prințul Bernhard al Olandei, au jucat un rol crucial în această rețea de conexiuni, întrucât au fost la cârmă de la începuturile sale în 1961. Pe lângă altețele regale, se pare că mișcarea de conservare i-a datorat mai mult fratelui lui Aldous Huxley, Julian, decât oricărei alte persoane. Co-fondator atât al WWF-IUCN, cât și un supus loial al Coroanei, Sir Julian Huxley, a întruchipat personal aceste două curente prin articolele sale despre degradarea habitatelor și a faunei sălbatice din Africa de Est, publicate în presa britanică la acea vreme.

La fel ca partenerii săi regali, el dădea vina pe umanitate. Sir Julian Huxley suferea de-o singură obsesie: controlul populației, pe care îl numea „problema epocii noastre”. Mai mult decât atât, în documentul fondator al UNESCO din 1946, el susține eugenia, spunând că inimaginabilul ar putea cel puțin deveni imaginabil într-o zi:

„Astfel, chiar dacă este adevărat că orice politică eugenică radicală va fi timp de mulți ani imposibilă din punct de vedere politic și psihologic, va fi important ca UNESCO să se asigure că problema eugenică este examinată cu cea mai mare atenție și că opinia publică este informată cu privire la problemele aflate în joc, astfel încât multe dintre lucrurile care sunt acum de neconceput să poată deveni măcar de conceput” (vezi Julian Huxley, UNESCO: its purpose and its philosophy, p. 21).

Pentru membrii familiei regale, cât și pentru funcționarii, Max Nicholson și Julian Huxley, guvernul mondial era răspunsul, iar conservarea vieții sălbatice, împreună cu politica eugenică, reprezentau o cale către atingerea acestui obiectiv. În felul acesta, inimaginabilul devine imaginabil sub forma „viziunii verzi” și a „cruciadei verzi” – o nouă ideologie pentru mase:

„Sub pretextul «conservării naturii», WWF-IUCN s-a dedicat, de fapt, pentru: 1) reducerea populației lumii, în special în sectorul în curs de dezvoltare și 2) de a se asigura că controlul materiilor prime mondiale rămâne în mâinile unui număr mic de multinaționale, în mare parte britanice (sau anglo-olandeze). Purtătorii de cuvânt ai WWF-IUCN au afirmat în repetate rânduri că aceste două obiective necesită un guvern mondial” (EIR, Allen Douglas).

„Principalii colaboratori ai Prințului Philip în lansarea WWF ca ramură de finanțare și operațiuni la nivel mondial a Uniunii Internaționale pentru Conservarea Naturii au fost Sir Julian Huxley și Max Nicholson, ambii susținători fervenți ai eugeniei și purificării rasiale. De fapt, Huxley era președintele Societății de Eugenie când a co-fondat WWF. Mai întâi, ca șef al Organizației Națiunilor Unite pentru Educație, Știință și Cultură (UNESCO), iar mai târziu ca fondator al WWF, Huxley a predicat necesitatea reînvierii științei rasiale și misiunea urgentă de „sacrificare a turmei umane” – în special a raselor cu pielea mai închisă la culoare din Africa și America de Sud.

(…) Metoda pe care Huxley și alții au conceput-o pentru a-i forța pe oameni „să gândească inimaginabilul” a fost înlocuirea ideii de eugenie cu ideea de ecologism. Huxley, Prințul Philip și ceilalți, însă, au înțeles că, în modul lor de gândire, cei doi termeni erau interşanjabili. În timpul unui turneu în Africa din 1960, în ajunul lansării WWF, Huxley s-a lăudat deschis că mișcarea ecologistă va fi principala armă folosită de oligarhia britanică pentru a impune o ordine mondială malthusiană peste cadavrul sistemului statului-națiune și, cel mai important, peste Statele Unite” (EIR, Jeffrey Steinberg, 1997).

În 1961, WWF a luat naștere, iar odată cu ea, visele Africii de independență au fost spulberate.

Un Trust pentru conservarea naturii: controversatul Club al celor „1001”

Nu doar să gândească inimaginabilul, ci și să-l facă real – aceasta a fost sarcina lui Julian Huxley. Ideea lui Huxley de a înlocui eugenia cu ecologismul nu ar fi fost posibilă dacă nu ar fi avut ușile deschise la casele regale. Acest lucru s-a văzut când, câțiva ani mai târziu, Prințul Philip s-a asociat cu Prințul Bernhard al Olandei și cu omul de afaceri african Anton Rupert pentru a crea un alt „mecanism de finanțare” care să răspândească activitățile Fondului Mondial pentru Natură (WWF, implicit al IUCN) și, odată cu acesta, viziunea verde în lume:

„Pentru a răspândi și mai mult activitatea WWF, în 1970, Prințul Philip a făcut echipă cu un fost ofițer SS, Prințul Bernhard al Olandei, deja un jucător important al WWF, cu scopul de a crea un mecanism permanent de finanțare pentru numărul tot mai mare de fronturi ecologiste apărute, de a aduna drojdia contraculturii de la sfârșitul anilor ’60 și a o folosi ca soldați de asalt ai noului fascism «verde»” (EIR, Jeffrey Steinberg).

Astfel, în anul următor, Clubul celor «1001» apăruse ca un al doilea „mecanism de finanțare” pentru conservare. Și poate că a fost al treilea de fapt, având în vedere că „în 1968, Aurelio Peccei, fostul director executiv al Fiat (președintele Fiat, Gianni Agnelli, a fost membru fondator al Clubului 1001), fondase Clubul de la Roma, o altă organizație la care se participa doar pe bază de invitație, pentru a promova un nou tip de malthusianism, specific erei computerelor”:

„1001: A Nature Trust, cunoscut printre membrii săi drept «Clubul celor 1001», a fost creat ca o asociere la binecunoscutul Grup Bilderberg al Prințului Bernhard, societatea secretă din epoca Războiului Rece formată din lideri oligarhici nord-americani și europeni – 1.001 de asociați personali apropiați ai Prințului Bernhard și ai Prințului Philip au fost «invitați» să se alăture Clubului 1001, contra unei taxe inițiale de 10.000 de dolari per persoană. Majoritatea membrilor au fost aleși din consiliile de administrație ale principalelor carteluri de materii prime din cadrul Clubului Insulelor, bănci, companii de asigurări și trusturi familiale” (EIR, Jeffrey Steinberg).

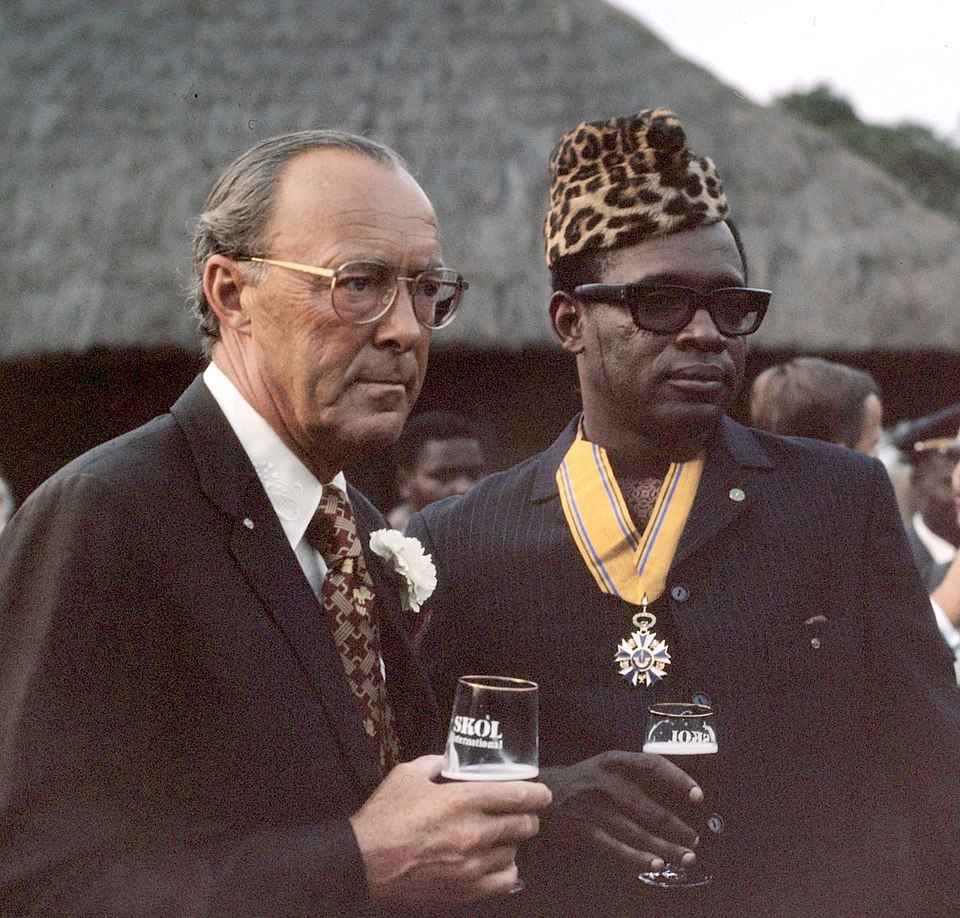

„În ceea ce privește filantropia de mediu, exemplul rețelei Bilderberg este deosebit de important datorită implicării Prințului Bernhard, deoarece acesta a fost, de asemenea, profund implicat în conservarea naturii prin intermediul WWF International, al cărui președinte a fost între 1962 și 1976. Împreună cu prietenul său de-o viață din Africa de Sud, magnatul de afaceri Anton Rupert, Prințul Bernhard a dezvoltat conceptul «Clubului 1001» în 1970. Clubul avea drept scop de a atrage 1000 de oameni bogați din întreaga lume pentru a dona 10.000 de dolari pentru a ajuta WWF să își acopere costurile generale. Membrul numărul 1001 a fost însuși Prințul Bernhard. Probabil nu va fi o surpriză faptul că mulți dintre membrii săi erau persoane din sectorul bancar, alte sectoare de afaceri, informații, armată și șefi de stat, adică rețelele care au participat și la conferințele Bilderberg (Aalders, 2009). În plus, un număr destul de mare de membri făceau parte din sectorul de afaceri sud-african care oficial fuseseră obiectul unui boicot al ONU (Spierenburg și Wels, 2010)” (Maano Ramutsindela, Marja Spierenburg și Harry Wels, 2011, p. 47).

În 1971, Uniunea Internațională pentru Conservarea Naturii (IUCN) avea cel puțin trei mecanisme majore de finanțare pentru mișcarea ecologistă: Fondul Mondial pentru Natură (WWF, 1961), Clubul de la Roma (1968) și Clubul celor «1001» (1970/1). Să nu uităm de Școala Wilderness a lui Ian Player (1965), care, din anii ’74, a fost transformată de asemenea într-o fundație care strânge bani pentru conservare, anume International Wilderness Leadership Foundation.

Întrebările enigmatice de aici sunt: „Cine donează pentru ce cauză de mediu și de ce?” „Ce primesc cei «1001» pentru banii lor, în afară de prestigiul privat și privilegiul de a lua masa cu Prințul Bernhard sau cu Ducele de Edinburgh?” Parafrazându-l pe Joel van der Reijden, din moment ce Clubul 1001 servește drept nucleu intern al Fondului Mondial pentru Natură, are vreunul dintre fondatorii sau recruții săi vreo implicare în grupurile de conservare? (apud. Private Eye, 1980; Joel van der Reijden, The 1001 Club, 2005; Maano Ramutsindela, Sponsoring nature, 2011, p. 16).

Dacă ne uităm la lista membrilor acestor fundații și cluburi elitiste, vedem că, în mare parte, nu au nicio legătură cu mediul. Printre membrii lor se numără reprezentanți ai caselor regale din Europa, manageri de bănci și companii multinaționale din întreaga lume dar nu ecologiști. Oameni precum David Rockefeller, Robert McNamara, Gianni Agnelli, Anton Rupert sau familia Rothschild aparțin sectorului bancar, lumii afacerilor și politicii. Ei nu fac parte din ONG-urile de mediu:

„Rupert, prieten de-o viață al prințului Bernhard, era în general considerat cel mai important om de afaceri din Africa de Sud, fondatorul și președintele companiei de tutun Rembrandt, șeful Rothmans International și unul dintre cei mai bogați oameni din Africa de Sud. În prima parte a carierei sale, Rupert a fost strâns asociat al Broederbond, societatea secretă naționalistă africană. La sugestia prințului Bernhard (în 1968) de a înființa o filială națională, Rupert a înființat filiala sud-africană a WWF, Southern African Nature Foundation, al cărei președinte a devenit, convingând oamenii de afaceri sud-africani să se alăture consiliului său de administrație.

Mulți dintre membrii Clubului 1001 proveneau din sectorul bancar, alte sectoare de afaceri, serviciile de informații și armată sau erau șefi de stat. O parte dintre membrii Clubului 1001 făceau parte din sectorul de afaceri sud-african, care a făcut obiectul unor sancțiuni internaționale în timpul guvernului apartheid. Prin urmare, existau legături specifice între părți ale rețelei globale de elită și conservarea vieții sălbatice prin președinția Prințului Bernhard de la WWF International, precum și legături explicite ale WWF International cu Africa de Sud în domeniul filantropiei de mediu” (Wikipedia, The 1001: A Nature Trust. Vezi și Afrikaner Broederbond).

Anton Rupert a venit cu ideea înființării clubului, iar economistul belgian Charles de Haes, care era director general al WWF în ’75 și lucra ca director executiv la principala companie a lui Rupert, Rothmans, a întocmit o listă inițială de recrutare la cererea prințului Bernhard. Un raport foarte scurt din The Times, precum și o sursă divulgată a Raportului intern al celor «1001», confirmă faptul că altețele regale organizau recepții pentru a recruta membrii din țările lor. Cel mai probabil, același lucru s-a întâmplat și cu bancherii, și oamenii de afaceri:

„Un raport foarte scurt din 1978 din The Times confirmă faptul că Prințul Philip a dat o recepție la Castelul Windsor pentru membrii Clubului 1001. Un raport intern confidențial al Clubului 1001, divulgat prin scurgere de informații, confirmă, de asemenea, că Prințul Bernhard organiza în mod regulat recepții la Palatul Soestdijk pentru membrii olandezi ai Clubului 1001 și că Regele Juan Carlos își organiza propriile recepții în Spania pentru membrii spanioli” (Joel van der Reijden, The 1001 Club). Aceste recepții exclusiviste de recrutare arată un singur lucru: „că «1001» este organizat în același mod ca multe alte cluburi recunoscute, inclusiv prestigioasa Pilgrims Society”, „care este strict anglo-americană”, remarcă Joel van der Reijden.

Pe de altă parte, unii dintre membri, Gianni Agnelli și David Rockefeller, de exemplu, formau un mic grup de colegi Bilderbergeri, fapt care a făcut ca vocile critice să afirme că «1001» ar fi putut apărea și din Grupul Bilderberg/Comitetul Director de la sfârșitul anilor ’60. Fundațiile filantropice, cluburile și organizațiile precum Grupul Bilderberg au fost mereu parte integrantă a rețelelor de elită și au jucat un rol esențial în adunarea oamenilor în jurul unei viziuni comune:

„Legăturile specifice dintre (părți ale) rețelei globale de elită Bilderberg și conservarea vieții sălbatice prin președinția Prințului Bernhard de la WWF International, și legăturile explicite ale WWF International cu Africa de Sud în domeniul filantropiei de mediu fac din Africa de Sud un exemplu deosebit de puternic pentru explorarea conexiunilor istorice Sud-Nord în filantropie”, și de a le pune sub semnul întrebării, am adăuga (Maano Ramutsindela, Sponsoring nature, 2011, p. 48).

Dintre toate grupurile sau cluburile elitiste din întreaga lume, Clubul 1001 ar putea fi cel mai controversat din pricina unui procent de membri care au legături strânse cu CIA, Mossad, dictaturile din lumea a treia, spălarea de bani, traficul de arme, traficul de droguri, traficul de aur, mergând până la „Caracatița”, adică Mafia, iar procentajul respectiv nu pare a fi chiar atât de mic.

Din acest motiv, ne întrebăm: 1) Ce au câștigat făcând parte din Club, în afara prestigiului, desigur, oameni precum Mobutu Sese Seko, fostul dictator al Zairului, și Agha Hasan Abedi, fostul președinte al Băncii de Credit și Comerț Internațional, responsabil pentru cea mai mare fraudă din istoria financiară mondială? 2) Paravanul căror afaceri murdare servește, de fapt, clubul? (vezi Teorii Incredibile, Ei sunt cei 1% care controlează resursele lumii * Clubul 1001, Cel mai secret și ciudat club din lume, la https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Evw9MoUskeI. De asemenea, Clubul celor 1001 și Agenda de încălzire globală indusă de om – Cine stă în spatele propagandei, la https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4v7KirpFFtU).

Ana-Maria Caminski

Corespondent in Romania, pentru NASUL TV Canada

Quo Vadis, or where are we going with sustainable development? (Third part)

When ‘Operation Rhino’ began in Africa, nobody thought it would turn into a Revolution. Although there were no visible signs of underground revolutionary currents, the environmental conservation movement led to a Green Revolution in Africa, spreading later worldwide. One of the pioneer figures was Dr. Ian Player, founder of Wilderness School[1] (also known as the WILD Foundation), without whom the ecological movement could not be understood or even conceived.

Africa has been a battlefield for centuries, ever since Cecil Rhodes coveted it for its riches. The idea that the superior white man, usually a tycoon, should come up with ‘better wildlife management’ is as old as the diamond rush of Rhodes and the British South Africa Company. Still, the total stripping of Africa’s natural resources is something that even Rhodes and his company did not achieve in the 19th century. Although he dreamed of annexing the planets, perhaps the savage continent too (see Wikipedia, Cecil Rhodes).

Background of the Green Revolution

Respect for nature is something that Africans did not have to learn from other civilizations. Nicholas Arthur Steele has quite well expressed this at the 4th World Wilderness Congress:

“The Zulu people have a tradition of understanding nature. Their conservation awareness goes back to the foundations of their society. Because they lived close to nature, they lived in harmony with it, and a balance was maintained between man and his environment. But this balance was lost when the white man arrived with his guns, his need for trade, and, eventually, his soldiers, farmers, and city builders. A new way of life, new priorities, and new issues have developed” (see Nick Steele, KWAZULU—CONSERVATION IN A THIRD WORLD ENVIRONMENT, in the For the Conservation of Earth: Proceedings of the 4th World Wilderness Congress, at https://wild.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/For-the-Conservation-of-Earth_Part_1.pdf).

A nature conservationist and close friend of Ian Player, Nick Steele[2] was another key character in Operation Rhino. Next to their Zulu mentor, Magqubu Ntombela, they were at the forefront of the conservation movement in Africa. Otherwise said, they formed the visible façade.

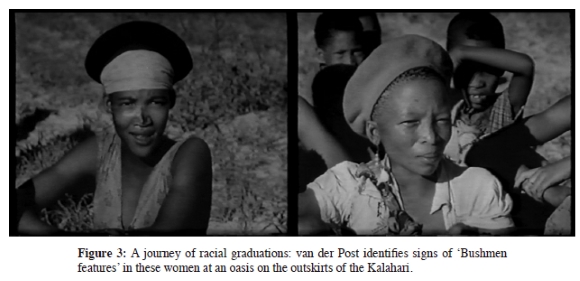

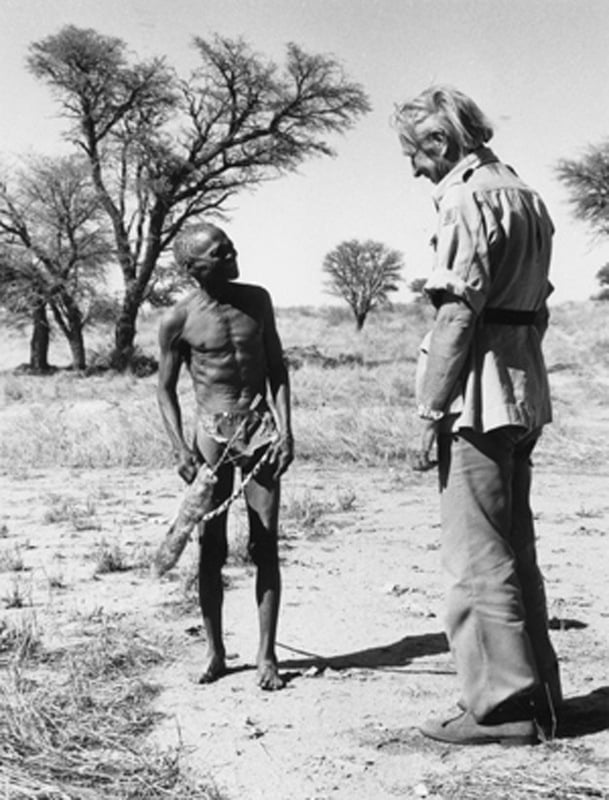

Less visible figures also joined the movement. Sir Laurens van der Post, the liaison with the British royal highnesses, with whom Ian Player would establish the first World Wilderness Congress in 1977 in Johannesburg, also played the role of a spiritual guide, albeit more discreetly. We might say that he and the British aristocracy were part of the invisible façade. Although the British and Dutch aristocracies have been involved in environmental conservation policy since the founding of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in 1961. But how did the conservation movement begin in Africa? Did it have any ideological implications from the beginning? (Wikipedia, Laurens van der Post)

According to the research paper ‘Sponsoring nature’, the Cold War geopolitics in the region of South Africa provide a useful platform for interrogating its conservation policy and sponsorship. Additionally, it provides a useful lens through which we can understand the intricate web of relationships and interests among different actants spread across continents, yet unified by a common vision. Vision that initially seemed to be concerned only with environmental protection, and which later emerged from the need (or rather, the fear) to ward off the spread of communism in the region (Maano Ramutsindela, Marja Spierenburg, and Harry Wels, 2011, pp. 45, 49).

The first fund of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature

Wilderness School was revolutionary in Africa. Nevertheless, the unifying worldview did not belong to it. The Wilderness School (later the WILD Foundation) followed a similar path to the World Wildlife Fund, namely, aiming to raise funds that would significantly expand the operations of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Together, they were like sister organizations unified by a common vision in a huge Octopus:

“The World Wildlife Fund (WWF, now the World Wide Fund for Nature) was founded in 1961 for one stated purpose: to raise money to drastically expand the operations of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Established in Gland, Switzerland, in 1948 on a British Foreign Office-drafted constitution, the IUCN today boasts that it is the largest „professional” international conservation organization, as of 1994 comprising 68 states, 103 governmental agencies, and over 640 non-governmental organizations, „many of global reach” ” (EIR, Allen Douglas, 1994).

A lesser-known fact is that the British Monarchy was behind them from the beginning:

“The WWF-IUCN is a spin-off of two of Britain’s leading imperial institutions: the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire (now the Fauna and Flora Preservation Society, FFPS, whose patron is the Queen), which laid the groundwork for the game parks throughout Africa; and the Eugenics Society”. “What became the WWF took shape in the pre-World War II period in the Political and Economic Planning satellite of a Rhodes-descended Foreign Office think-tank, the Royal Institute of International Affairs. Its „planning” focused on eugenics, raw materials control, and world-government; its two top officials, Max Nicholson and Julian Huxley, later founded both the IUCN and the WWF” (Ibid.).

The crowned heads, such as Prince Philip and Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, played a crucial role in this web of connections, as they have been at the helm since its inception in 1961. Besides the royal highnesses, it seems that the conservation movement owed more to Aldous Huxley’s brother, Julian, than to any other. Co-founder of both the IUCN and the WWF, and a loyal servant of the Crown, Sir Julian Huxley, personally embodied these two currents through his articles about the degradation of habitats and wildlife in East Africa, published in the British press at the time[3].

Alike his royal partners, he blamed humanity for it. Sir Julian Huxley suffered from one obsession: population control, which he called ‘the problem of our age’. More than that, in the UNESCO founding document from 1946, he stands for a eugenic policy, by saying that the unthinkable may at least become thinkable someday:

“Thus, even though it is quite true that any radical eugenic policy will be for many years politically and psychologically impossible, it will be important for Unesco to see that the eugenic problem is examined with the greatest care, and that the public mind is informed of the issues at stake so that much that now is unthinkable may at least become thinkable” (Julian Huxley, UNESCO: its purpose and its philosophy, p. 21).

For the royalties, as to their top officials, Max Nicholson and Julian Huxley, the One-World government was the answer, and wildlife conservation, along with eugenic policy, was a pathway to achieving this goal. In this way, the unthinkable becomes thinkable in the form of the ‘green vision’ and ‘green crusade’ – a new ideology[4] for the masses:

“Under the cover of „conserving nature”, the WWF-IUCN has in fact dedicated itself to l): reduce the world’s population, particularly in the developing sector, and 2) ensure that control of the world’s raw materials remains in the hands of a tiny handful of largely British (or Anglo-Dutch) multinationals. These two goals, WWF-IUCN spokesmen have repeatedly stated, require a world government” (EIR, Allen Douglas).

“Prince Philip’s principal collaborators in launching the WWF as a funding and worldwide operations arm of the IUCN were Sir Julian Huxley and Max Nicholson, both ardent advocates of eugenics and racial purification. In fact, Huxley was president of the Eugenics Society when he co-founded the WWF. First, as head of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and later as a WWF founder, Huxley preached the need to revive race science and the urgent mission of „culling the human herd”–particularly of the darker-skinned races of Africa and South America.

(…) The method Huxley and others devised for forcing people to „think the unthinkable”, was to replace the idea of eugenics with the idea of environmentalism. Huxley, Prince Philip, and the others, however, understood that, in their way of thinking, the two terms were interchangeable. During a 1960 tour of Africa, on the eve of the launching of the WWF, Huxley openly boasted that the ecology movement would be the principal weapon used by the British oligarchy to impose a Malthusian world order over the dead body of the nation-state system, and, most importantly, the United States” (EIR, Jeffrey Steinberg, 1997).

In 1961, the WWF was born, and with it, Africa’s dreams of independence were shattered.

A Nature Trust for conservation: the controversial Club of the ‘1001’

Not only to think the unthinkable, but also to make it real – this was the task of Julian Huxley. Huxley’s idea of replacing eugenics with environmentalism[5] wouldn’t have been possible if he hadn’t had the open doors at the royal houses. This was seen when, some years later, Prince Philip associated with Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands and the African businessman, Anton Rupert, to create another ‘funding mechanism’ that would spread the activities of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF, implicitly of IUCN) and, with it, the green vision in the world:

“To further spread the work of the WWF, in 1970, Prince Philip teamed up with a former SS officer, Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, already a prominent player in the WWF, to create a permanent funding mechanism for the growing number of ecology fronts being spawned, to scoop up the dregs of the late-1960s counterculture, and deploy them as the storm-troopers of the new „green” fascism” (EIR, Jeffrey Steinberg)[6].

Thus, next year, the ‘1001 Club’[7] appeared as a second ‘funding mechanism’ for the conservation. And maybe it was the third in reality, having in mind that „in 1968, Aurelio Peccei, a former executive of Fiat (Fiat President Gianni Agnelli was a charter member of the 1001 Club), founded the Club of Rome, another by-invitation-only organization, to peddle a new, computer-age brand of Malthusianism”:

“The 1001: A Nature Trust, known among its members as the „1001 Club”, was created as an adjunct to Prince Bernhard’s well-known Bilderberg Group, the Cold War-era secret society of leading North American and European oligarchical insiders–1,001 close personal associates of Prince Bernhard and Prince Philip were „invited” to join the 1001 Club at an initial fee of $10,000 per person. The bulk of the members were drawn from the boards of directors of the leading Club of the Isles raw materials cartels, banks, insurance companies, and family trusts” (EIR, Jeffrey Steinberg).

“In relation to environmental philanthropy, the example of the Bilderberg network is of particular significance because of the involvement of Prince Bernhard, as he has also been deeply engaged with nature conservation through WWF International, of which he was president between 1962 and 1976. Together with his lifelong Afrikaner friend in South Africa, business tycoon Anton Rupert, Prince Bernhard developed the concept of the ‘1001 Club’ in 1970. The club was meant to attract 1000 wealthy people from around the globe to donate $10,000 to help WWF cover its overhead costs. Member number 1001 was Prince Bernhard himself. It will probably not come as a surprise that many of its members consisted of persons from the banking sector, other business sectors, intelligence, the military, and heads of states, i.e. the networks that also participated in the Bilderberg conferences (Aalders, 2009). Furthermore, quite a number of the members were part of the South African business sector that officially was the subject of a UN boycott (Spierenburg and Wels, 2010)” (Maano Ramutsindela, Marja Spierenburg, and Harry Wels, 2011, p. 47).

In 1971, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) had at least three major financing mechanisms for the ecology movement: World Wildlife Fund (WWF, 1961), Club of Rome (1968), and Club of ‘The 1001’ (1970/1). Let’s not forget Ian Player’s Wilderness School (1965), which, since ’74s, has also been transformed into a foundation that raises money for conservation, namely the International Wilderness Leadership Foundation.

The puzzling questions up here are: ‘Who gives for which environmental cause and why?’ ‘What do the ‘1001’ get for their money apart from private prestige and the privilege of dining with Prince Bernhard or the Duke of Edinburgh?’ And, by paraphrasing Joel van der Reijden, since the 1001 Club serves as the inner core of the World Wide Fund for Nature, do any of its founders or recruits have any involvement with conservation groups? (apud. Private Eye, 1980; Joel van der Reijden, The 1001 Club, 2005; Maano Ramutsindela, Sponsoring nature, 2011, p. 16).

If we look up at the membership list of these elitist foundations and clubs, we see that they mostly have nothing to do with the environment. Their membership includes representatives of the royal houses of Europe, managers of banks and multinational companies from around the world, but not environmentalists[8]. People like David Rockefeller, Robert McNamara, Gianni Agnelli, Anton Rupert, or the Rothschilds belong to the banking sector, business world, and politics. They are not part of environmental NGOs:

“Rupert, a lifelong friend of Prince Bernhard, was generally regarded as South Africa’s leading Afrikaner businessman, the founder and chairman of the Rembrandt tobacco company, the head of Rothmans International, and one of the richest men in South Africa. In the earlier part of his career, Rupert was closely associated with the Afrikaner Broederbond, the Afrikaner nationalist secret society. At the suggestion of Prince Bernhard (in 1968) to found a South African national branch of the WWF, Rupert set up the South African chapter of the WWF, the Southern African Nature Foundation, of which he became the president, persuading South African businessmen to join its board of trustees.

Many of the 1001 Club members were from the banking sector, other business sectors, intelligence, and the military, or were heads of state. A number of the 1001 Club members were part of the South African business sector, which was the subject of international sanctions during apartheid. Therefore, particular linkages existed between parts of the global elite network and wildlife conservation through the presidency of Prince Bernhard of WWF International, as well as explicit links of WWF International to South Africa in the field of environmental philanthropy” (Wikipedia, The 1001: A Nature Trust. Also, see Afrikaner Broederbond).

Anton Rupert came up with the idea of establishing the club, and the Belgian economist Charles de Haes[9], who was the Director General of the WWF by the ’75s and worked as an executive of Rupert’s main company, Rothmans, drew up an initial recruitment list at the request of Prince Bernhard. A very brief report from The Times, as well as a leaked source of the 1001s internal report, confirms that the royalties organized receptions to recruit members from their countries. It is most likely that the same went for the bankers and businessmen:

“A very brief 1978 report in The Times confirms that Prince Philip gave a reception at Windsor Castle for 1001 Club members. A leaked, confidential internal report of the 1001 Club furthermore confirms that Prince Bernhard regularly organized receptions at Soestdijk Palace for Dutch 1001 Club members, and that King Juan Carlos organized his own receptions in Spain for Spanish members” (Joel van der Reijden, The 1001 Club). These exclusivist recruiting receptions show one thing: “that the 1001 Club is organized in the same way as many other establishment clubs, including the prestigious Pilgrims Society”, “which is strictly Anglo-American”[10], remarks Joel van der Reijden.

On the other side, some of the members, Gianni Agnelli and David Rockefeller, for example, form a small group of fellow Bilderbergers, a fact that made critical voices say that the ‘1001’ might have emerged as well from the Bilderberg/Steering committee during the late of the ’60s[11]. Philanthropic foundations, clubs, and organizations like the Bilderberg Group have always been part and parcel of elite networks, and have been instrumental in getting people together around a common vision:

“The particular linkages between (parts of) the global Bilderberg elite network and wildlife conservation through the presidency of Prince Bernhard of WWF International, and the explicit links of WWF International to South Africa in the field of environmental philanthropy, make South Africa a particular strong case in point for exploring historical South-North connections in philanthropy”, and question them we will add (Maano Ramutsindela, Sponsoring nature, 2011, p. 48).

From all the elitist groups or clubs around the globe, the 1001 Club might be the most controversial because of a percentage of members that have close ties to the CIA, the Mossad, Third World dictatorships, money laundering, arms dealing, drug trafficking, gold trafficking, to the ‘Octopus’, namely the Mafia, and that looks not to be that small indeed[12].

Because of this, we wonder: 1) What people like Mobutu Sese Seko, the ex-dictator of Zaire, and Agha Hasan Abedi, the former president of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, responsible for the biggest fraud in world financial history, gained by being part of the Club besides the prestige, of course? 2) The paravan of whose dirty business the club actually serves?

Endnotes

[1] Founded in 1965 by Ian Player, Wilderness School changed its designations several times, also the status from a simple training school to an international foundation. Starting in 1974, it became the International Wilderness Leadership Foundation Inc., a concept that expanded into what would be known as the WILD Foundation in 1988. Today, IWLF (namely, the WILD Foundation) is a member of IUCN, also a founding member of Wilderness Foundation Global (WFG), an international alliance, or a consortium of independent, like-minded organizations: “The IWLF grew out of the seminal experience of the Wilderness Leadership School, founded in 1965 by Ian Player. In the last 25 years, „The School” has taken over 8,000 people, in groups of no more than six people at a time, into the African wilderness on „trail”, or a hiking safari. Corporate executives, political leaders, royalty, teachers, and school children of all races, religions, and many nationalities have had this experience”.

“In 1974, the ideas of conservation that inspired the Wilderness Leadership School expanded into the concept that became the WILD Foundation and WILD’s sister organizations in the Wilderness Network. Laurens van der Post worked closely with Player in the early days of WILD and was a founding member of the board of directors, serving until 1987. Originally named the International Wilderness Leadership Foundation, the organization began doing business as the WILD Foundation in 1988. WILD has been a member of the World Commission on Protected Areas (International Union for Conservation of Nature) since 1988, and founder/co-chair of the IUCN Wilderness Specialist Group” (IWLFs Newsletter, The Leaf: Wilderness Leadership School, p. 7. Also, see Wikipedia, WILD Foundation, and the following links https://wild.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/12/1_vol1_issue1_1988.pdf, https://wildernessfoundationglobal.org/).

[2] In an eulogy, Ian Player emphasizes this by saying Nick Steele initiated the conservancy movement, which has then spread to all of southern Africa, and that without the mentorship of Magqubu Ntombela, they could never have achieved what they did (see Ian Player’s eulogy delivered at Nick Steele’s funeral on 4 June 1997, at the following link https://natalia.org.za/Files/27/Natalia%20v27%20obituaries%20Steele.pdf).

With reference to this, see also the portrayal of ‘Nick Steele (1933-1997): Conservationist and Anti-Communist’, in Sponsoring nature, §Chapter 3. The South-North Connections: World Systems Theories and Elite Networking:

“Nick Steele’s life as a conservationist can be sketched on the basis of his involvement with the conservation and protection of the rhinoceros. At the beginning of his career, as a young game ranger in Umfolozi in the late 1950s and 1960s, he became the right-hand man of Ian Player in one of the most ambitious rhino conservation projects then seen, Operation Rhino. (…) Operation Rhino surely ‘catapulted the provincial conservationists to fame … [and] opened global horizons’ (Draper, 1998, p.806). For Nick Steele, this meant an entry into the world and (elite) networks of nature conservation. Not only in the proliferation of the private wildlife conservancy movement from South Africa to its neighboring countries in the 1990s (cf. Wels, 2003) but throughout Steele’s personal career in nature conservation, rhino conservation was key herein” (Maano Ramutsindela, Marja Spierenburg, and Harry Wels, 2011, p. 53).

[3] “Inspired by a series of articles in a UK newspaper written by Sir Julian Huxley about the destruction of habitat and wildlife in East Africa, businessman Victor Stolan pointed out the urgent need for an international organization to raise funds for conservation. The idea was then shared with Max Nicholson, Director General of the British government agency Nature Conservancy, who enthusiastically took up the challenge. Nicholson was motivated in part by the financial difficulties facing the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and felt that a new fundraising initiative might help IUCN and other conservation groups carry out their mission. He drafted a plan in April 1961 that served as a basis for WWF’s founding, which was then endorsed by the executive board of IUCN in a document known as the Morges Manifesto” (with reference to this, to be seen WWF’s website, at https://www.worldwildlife.org/about/history/#:~:text=Prince%20Philip%2C%20the%20Duke%20of,the%20World%20Wildlife%20Fund%20family.&text=World%20Wildlife%20Fund%2C%20Inc.,becomes%20the%20logo%20for%20WWF.).

And “in 1948, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) was established, mainly by Sir Julian Huxley, a famous biologist. Later, in September 1961, Julian Huxley officially established the WWF, together with persons as Prince Bernhard, Prince Philip, and, less publicly known, Anton Rupert, a South African business magnate who came to serve as a member of the WWF International’s executive trustee council. Prince Philip was the founding president of WWF-UK and international president from 1981 to 1996. Prince Bernhard served as international president from 1962 to 1976, when the Lockheed (and repressed Northrop) Affair forced him to resign from both the WWF and Bilderberg” (Joel van der Reijden, The 1001 Club, at https://www.isgp-studies.com/1001. As well, see https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/1470/object/5138-11259857).

[4] As the EIR’s column remarked, the ‘green ideology’ of both institutions, the Fauna and Eugenics Society, as that of WWF, finds its roots in Francis Galton and Charles Darwin’s theories. Unlike his brother, Aldous Huxley, who took a distance from any movements, Julian Huxley was an open preacher of eugenics and of this new ideology of the conservation movement. Alongside his co-worker, Max Nicholson, Julian was one of the pioneer figures of the world environmental movement:

“The co-founder of both the, IUCN and the WWF, Sir Julian Huxley, personally embodied these two currents. He was obsessed with population control, which he called „the problem of our age”. He served on the British government’s Population Investigation Commission between World War I and World War II, was vice president of the Eugenics Society from 1937-44, and was its president when he founded the WWF in 1961. He also served as a vice president of „the Fauna”, as its aristocratic members still fondly call it.

The ideology of both institutions, and of their WWF spawn, dates in its modern form from Sir Francis Galton, who coined the term „eugenics”, and his first cousin, Charles Darwin, who in 1859 authored his infamous Origin of the Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life. Galton aimed to propagate the pseudo-scientific humbug of Darwinism’s „survival of the fittest” in the human arena, and so defined the aims of his „Race Betterment Movement” as: „To create a new and superior race through eugenics”, which would require the human race to be „culled”. The Darwin-Huxley tribe and its cousins have propagated this doctrine unceasingly over the past century and a half” (EIR, Allen Douglas. Also see Wikipedia, Julian Huxley).

Thus, we cannot say that the conservation movement started in Africa (as well as in the rest of the world) was outside of any ideological implication. Interesting that the movement started when Africa was preparing to gain its independence:

“In 1960, as much of Africa was preparing for independence, the 74-year-old Huxley took an arduous three-month tour of Africa, preaching that the newly independent states could not be trusted to „conserve wildlife”. Under that cover, and with the aim of subverting and destroying independence, Huxley and Nicholson linked up the following year with their royal soulmate, Prince Philip. The WWF was born” (see the Executive Intelligence Review (EIR), Allen Douglas, The WWF: race science and world government, at https://larouchepub.com/eiw/public/1994/eirv21n43-19941028/eirv21n43-19941028_026-the_wwf_race_science_and_world_g.pdf. Also, Max Nicholson, The Environmental Revolution: A Guide for the New Masters of the World, Hardcover, Jan 1, 1970).

[5] The ‘green vision’ took shape soon after WWII, against the backdrop of environmental destruction and the depletion of natural resources. Rather than replacing eugenics with environmentalism, Julian Huxley’s approach was more of a blending of both terms, along with the economy. Thus, through his method, he transformed the economy into what we may call today the ‘green economy’, which is much more ecologically oriented, and capitalism into something more sustainable. But this offered the military force a ‘green light’, meaning a free hand to expropriate the Negros from South Africa, also to torture and kill the poachers during the Operation Lock, and many years after (regarding the militant aspect of the conservation movement, see the study of Bram Büscher and Maano Ramutsindela, Green violence, 2015. As well as the essay of Stefan Bernhardt-Radu, Julian S. Huxley, the man who put eugenics into UNESCO, Dec 2, 2024, at the following link https://aeon.co/essays/julian-s-huxley-the-man-who-put-eugenics-into-unesco).

[6] In the ’60s, the dregs of counterculture were composed of rock, drugs, and sex – a strategy plan of a hidden psychological-warfare, initiated and led by the British top think-tank, Tavistock Institute (see Susan Welsh, EIRs Foreword, 1997). Also, the article of Jeffrey Steinberg: “Today, as the result of a 35-year effort, personally led by Prince Philip and his Dutch counterpart, Prince Bernhard, a worldwide eco-fascist structure is already well-entrenched throughout the globe, particularly within the British Commonwealth, and in the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund bureaucracies, whose stated purpose is to carry out levels of population genocide that would make Adolf Hitler’s crimes pale by comparison.

EIR first documented the role of Prince Philip as the „new Hitler” in „The Coming Fall of the House of Windsor”, on Oct. 28, 1994. Since then, EIR has published a series of in-depth stories, detailing aspects of the global eco-fascist apparatus and its links to the London-headquartered Club of the Isles financial oligarchy” (EIR, Jeffrey Steinberg, Tinny Blair Blares For Prince Philip’s Global Eco-Fascism, at http://american_almanac.tripod.com/tinny.htm, respectively https://larouchepub.com/eiw/public/1997/eirv24n29-19970718/eirv24n29-19970718.pdf).

[7] According to Joel van der Reijden, the founding of ‘The 1001’ lies in a mystery, it’s almost unknown. Nevertheless, it seems that Anton Rupert came up with the idea of establishing the club:

“As a result of this lack of information, the only official information available about this club – which the average person is very unlikely to stumble upon – is that it was established in the early seventies by individuals as Prince Bernhard, Anton Rupert, and Charles de Haes, and that every member paid a one-time fee of $10,000 to get lifetime membership. That’s about it. This almost total absence of public awareness seems odd, as the individuals visiting 1001 Club receptions often represent some of the biggest, most connected, and sometimes even most controversial, economic interests on the planet.

(…) Ten years later, in 1971, it was Anton Rupert who came up with the idea of establishing a club that would cover the administrative and fundraising aspects of the WWF headquarters in Switzerland. One line of reasoning went that, „with the ‘1001’ behind us, we haven’t got to worry about the national organizations giving us a hard time” ” (Joel van der Reijden, The 1001 Club: ‘The 1001: totally unknown’, and ‘1971-1974: creation of the 1001’, 2005).

[8] “Membership in the „1001 Club”, founded in 1971 by Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, consort to Queen Juliana of the House of Orange, is restricted to 1,001 persons at any given time and is by invitation only. All members pay a $10,000 initiation fee, which goes toward a $10 million trust to bankroll World Wildlife Fund operations. The club donated an office building in Gland, Switzerland, which currently houses the international headquarters of the WWF and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Initial members were handpicked by Prince Bernhard and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Membership includes representatives of the royal houses of Europe, officials of British Crown corporations, and prominent figures in international organized crime. Below is a sample of current and past members with brief biographical data” (EIR, Scott Thompson, The ‘1001 Club’: a nature trust, at https://larouchepub.com/eiw/public/1994/eirv21n43-19941028/eirv21n43-19941028_025-the_1001_club_a_nature_trust.pdf).

Relating to this, see also: “The membership of the 1001 Club largely consists of managers of banks and multinationals from around the world. Examples from past and present include Sir Eric Drake of British Petroleum, Sir Val Duncan of Rio Tinto, Harry Frederick Oppenheimer and Sidney Spiro of Anglo-American Corporation, the British and French Rothschilds, Michel David-Weill of Lazard, Laurance and David Rockefeller, Henry Ford II, Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza, Peter von Siemens, and Berthold Beitz of Krupp. Among the more remarkable members have been Salem bin Laden, Osama bin Laden’s older half-brother; Mobutu Sese Seko, the dictator of Zaire; BCCI founder and president Agha Hasan Abedi; Louis Bloomfield and Tibor Rosembaum; and the controversial businessman Nelson Bunker Hunt” (SourceWatch, 1001 Club, at https://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/1001_Club).

[9] “In January 1970, Rupert chaired the new fundraising committee and, working with Rothmans executive Charles de Haes, operationalized the plan to solicit 1,000 donors with personalized invitations from Prince Bernhard. De Haes was given broad authority for two years (while still paid by Rupert) to implement the plan.

Rupert and de Haes presented the plan to Peter Scott and Fritz Vollmar at Slimbridge. Rothmans’ designers created the club logo – a globe and the numbers 1001 embossed in gold – which was accepted by Bernhard. Club 1001 pins were manufactured by Garrard” (see Wikipedia, The 1001: A Nature Trust, and Charles de Haes).

“Earlier, already Anton Rupert had appointed the Belgian-South African economist Charles de Haes, who served as an executive of Rupert’s main company, Rothmans, as personal assistant to WWF president Prince Bernhard. For the first three years in this position, De Haes’ salary at the WWF was paid for by Rupert. Subsequently, Prince Bernhard and De Haes continued their cooperation in setting up the 1001 Club, once again respectively as president and secretary. De Haes drew up an initial recruitment list based on the connections of Prince Bernhard, with it being quite clear that Anton Rupert in South Africa, Prince Philip in Great Britain, and (future) King Juan Carlos all played important roles as well in the recruiting of members in their own respective countries. Looking at elite social networks per country, and comparing it to 1001 Club membership lists, it is clear that the same went for other countries as well” (Joel van der Reijden, The 1001 Club: ‘1971-1974: creation of the 1001’, 2005).

[10] “A careful analysis by ISGP reveals that about 35 percent of both the British and American 1001 Club members have also belonged to the Pilgrims Society. These overlapping members include some of the more connected individuals and families, such as the Astors, Mellons, Watsons, Bakers (historic Morgan agents), Rockefellers, Rothschilds, and members of the British royal family. This, of course, indicates that both the Pilgrims Society and 1001 Club have the same central core around which much of the West’s globalist establishment has organized itself during the 20th and early 21st century” (Joel van der Reijden, The 1001 Club: ‘Differences between the 1001 and the Pilgrims’, 2005).

[11] “The 1001 Club emerged out of the Bilderberg/Steering committee during the late 1960s. It centered around the chairman of that group, Bernhard von Biesterfeld. The founder, Bernhard von Biesterfeld, was a deep politician who was Bilderberg/Steering committee/Chairman for over 20 years. A small group of fellow Bilderbergers (Gianni Agnelli and David Rockefeller of the Steering committee and Marcus Wallenberg Jr.) were regular Bilderbergers in the late 1960s, and guest of the late 1960s Bilderbergs included others who became members of the 1001 Club, including Douglas Dillon, Henry Ford II, Thomas Jones, Cyril Kleinwort, Allen Lambert, Robert McNamara, Stavros Niarchos, Hans Merkle and Philip Mountbatten” (Wikispooks, The 1001 Club).

[12] To be seen, Joel van der Reijden, The 1001 Club: ‘Controversial members’. Also, Wikipedia, The 1001: A Nature Trust, next paragraph:

“In his book At the Hand of Man: Peril and Hope for Africa’s Wildlife Raymond Bonner criticized the WWF on charges of neocolonialist methods. In her review of his book, Ann O’Hanlon of the Washington Monthly, who called Bonner’s charges a „thorough indictment of WWF”, wrote: „The secret list of members includes a disproportionate percentage of South Africans, all too happy in an era of social banishment to be welcomed into a socially elite society. Other contributors include businessmen with suspect connections, including organized crime, environmentally destructive development, and corrupt African politics. Even an internal report called WWF’s approach egocentric and neocolonialist. (The report was largely covered up)”.

References

- Executive Intelligence Review (EIR). The WWF: race, science, and world government, by Allen Douglas. Issue of EIR Volume 21, Number 43, October 28, 1994. Web, PDF.

- Executive Intelligence Review (EIR). The ‘1001 Club’: a nature trust, by Scott Thompson. Issue of EIR Volume 21, Number 43, October 28, 1994. Web, PDF.

- Executive Intelligence Review (EIR). Tinny Blair Blares For Prince Philip’s Global Eco-Fascism, by Jeffrey Steinberg. Published online by the American Almanac, Issue of EIR Volume 24, Number 29, July 18, 1997. Web, PDF.

- Huxley, Julian. UNESCO: its purpose and its philosophy. Published by the Preparatory Commission of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation, 1946. Online by the UNESDOC Digital Library. Web, PDF.

- Institute for the Study of Globalization and Covert Politics (ISGP). The 1001 Club: Rockefellers, Rothschilds, Royals, Bechtels, Bin Ladens and Dictators Striving for a Sustainable Future, by Joel van der Reijden. Published online by ISGP-studies on Aug 14, 2005. Content updated on July 3, 2023. Web.

- Martin, Vance (ed.). For the Conservation of Earth: Proceedings of the 4th World Wilderness Congress. US, Denver, Colorado: Published by Fulcrum Publishing, Inc. Golden, September 1, 1988. Web, PDF.

- Newsletter of the IWLF. The Leaf. USA: No. 1, Dec 1988. Web, PDF.

- Ramutsindela, Maano, Marja Spierenburg, and Harry Wels. Sponsoring nature: environmental philanthropy for conservation. US, New York: Earthscan, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, 2011. Print.

- Ramutsindela, Maano, and Bram Büscher. Green violence: Rhino poaching and the war to save Southern Africa’s peace parks. Published by Oxford University Press, African Affairs, Volume 115, Issue 458, pages 1–22, on 24 December 2015. Web, PDF.

- Teorii Incredibile. Ei sunt cei 1% care controlează resursele lumii * Clubul 1001, Cel mai secret și ciudat club din lume, Jul 1, 2024. YouTube.

- Teorii Incredibile. Clubul celor 1001 și Agenda de încălzire globală indusă de om – Cine stă în spatele propagandei, Jul 3,2024. YouTube.

- Wikipedia. Afrikaner Broederbond. Web.

- Wikipedia. Cecil Rhodes. Web.

- Wikipedia. Charles de Haes. Web.

- Wikipedia. Julian Huxley. Web.

- Wikipedia. Laurens van der Post. Web.

- Wikipedia. The 1001: A Nature Trust. Web.

- Wikispooks. The 1001 Club. Web.